If you ask Prof. Yossi Garfinkel, head of the seven-year archaeological dig at Khirbet Qeiyafa in the Ella Valley, there is no question that 3,000 years ago there was a strong and independent Jewish Kingdom in the Land of Israel • The completion of the excavations, and the uncovering of an expansive royal palace last week, drives what may turn out to be the last nail in the coffin of Biblical Minimalism, which has tried to destroy the ancient tradition of a sovereign Jewish Kingdom in the Land of Israel

If you ask Prof. Yossi Garfinkel, head of the seven-year archaeological dig at Khirbet Qeiyafa in the Ella Valley, there is no question that 3,000 years ago there was a strong and independent Jewish Kingdom in the Land of Israel • The completion of the excavations, and the uncovering of an expansive royal palace last week, drives what may turn out to be the last nail in the coffin of Biblical Minimalism, which has tried to destroy the ancient tradition of a sovereign Jewish Kingdom in the Land of Israel

Yosef garfinkel and Saar ganor

For fifty years, between 1930 and 1980, any archaeological find in Israel was interpreted in line with the Biblical tradition. For instance, the finding of any fortified city from the Monarchical period was attributed to David and Solomon. Today it is clear that this was a simplistic and naïve approach, one which lacked a scientific basis. Modern research must date levels of settlement or structures based on the findings within them, such as pottery and imported vessels from other lands, and it is mainly best to rely on the dating method based on carbon-14.

As a counter response to the naïve approach, an opposing school developed in Copenhagen and Sheffield which entirely “forbade” the use of the Biblical tradition in the historical and archaeological study of the Land of Israel. According to this approach, the Biblical books were written only in later periods – hundreds of years after the events they describe – and they should therefore be seen as collections of legends lacking any historical basis. According to this new school, researchers may only use extra-Biblical historical sources, such as Egyptian, Assyrian and Babylonian royal stele or inscriptions unearthed in archaeological excavations. The total disqualification of the Biblical tradition was seen by these researchers as the sole legitimate scientific approach.

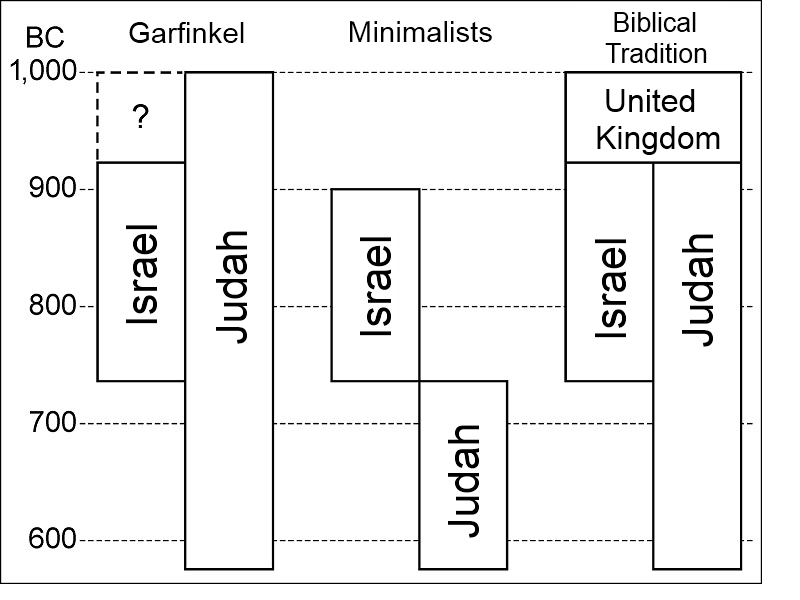

When we examine the Near Eastern inscriptions we know of, we find no mention of a United Monarchy; the Kingdom of Judah is also only mentioned in the days of the Assyrian King Sennacherib in 701 BC. Therefore, as we see in Illustration 1, the researchers of the new approach erased the United Monarchy as well as the entire early part of the Kingdom of Judah. In fact, this is also a simplistic and scientifically baseless approach, founded entirely on the single assumption that the Bible contains no historical memory. This assumption has in no way been proven. This worldview is commonly called the Minimalist approach.

Another approach has developed in Israel, mainly at Tel Aviv University, which can be called the Wild Imagination approach. Researchers of this approach selectively take data from the Biblical traditions and develop them into entirely imaginary theories which can be neither confirmed nor denied. In their opinion, David was an insignificant Biblical leader, while it was actually Saul who was a particularly important king. Thus, it was suggested that Saul was not killed in battle against the Philistines at the Gilboa, but in a battle against the Egyptian king Shishak. The absurdity is clear: according to the Biblical tradition, Shishak entered the land in the time of Rehavam, David’s grandson! Thus, with no justification, Saul’s dating was moved forward by a century. Although the Imaginary school selectively uses the Biblical traditions, it has accepted the basic conception that Judah became a kingdom only at the end of the eighth century BC, 300 years after David.

Yossi Garfinkel and Saar Ganour in Qeiyafa

It is against this background that one must understand the immense importance of the discoveries made at Khirbet Qeiyafa, excavated between 2007 and 2013, and where the seventh and last excavation season has concluded. I conducted the excavations together with Mr. Saar Ganour of the Israeli Antiquities Authority.

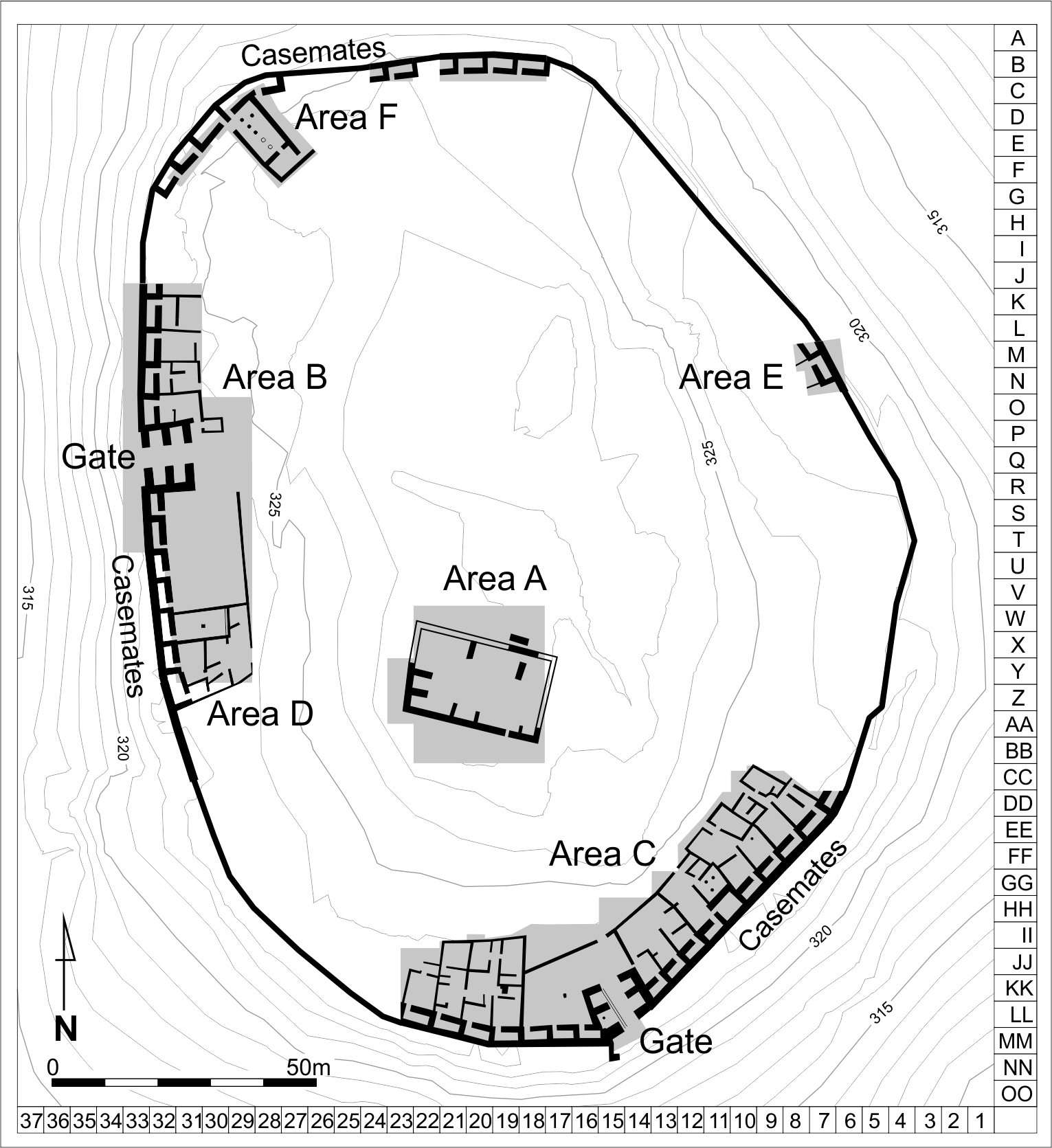

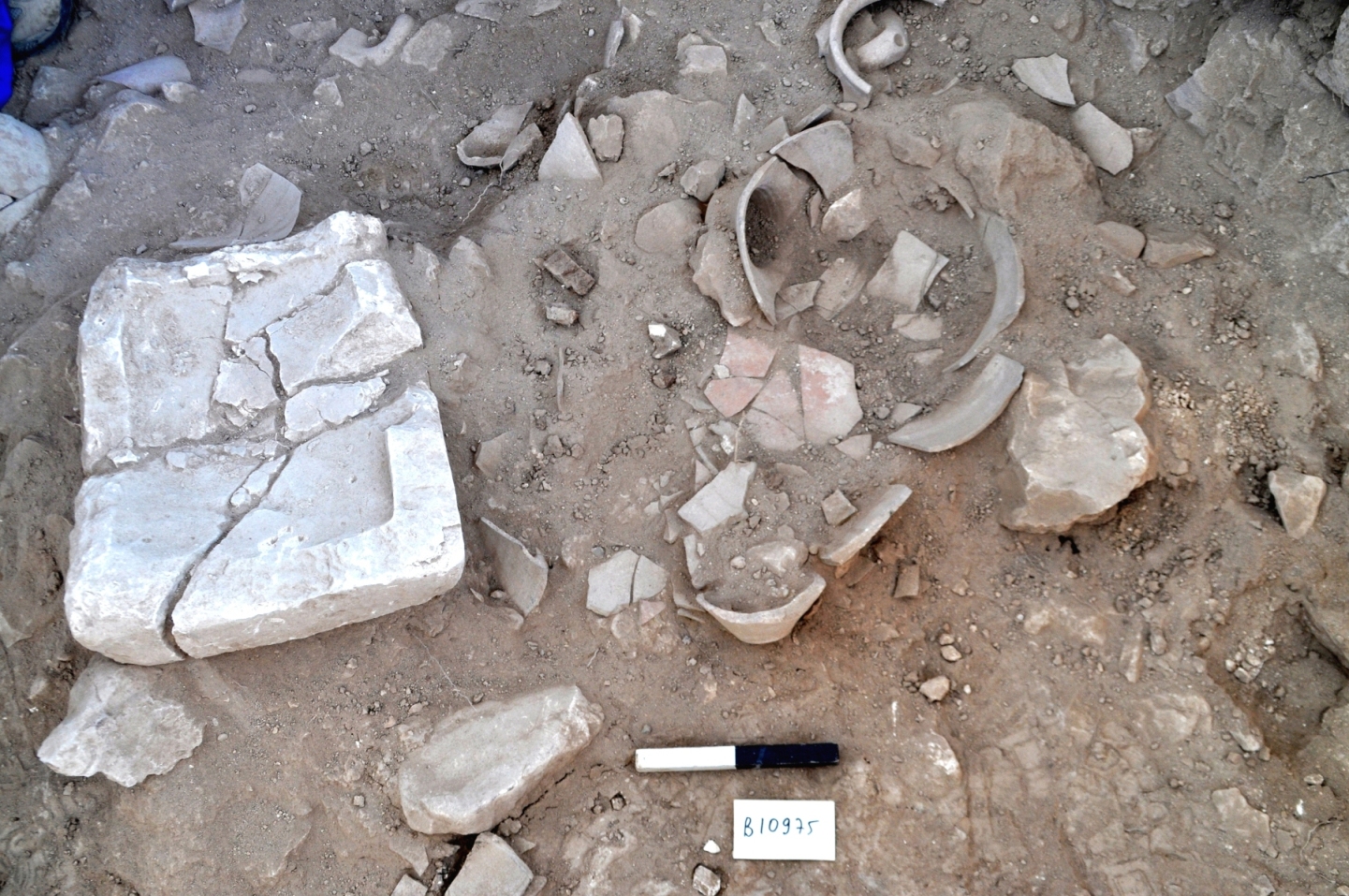

The excavations uncovered an exceptionally fortified city, whose defenses include stones weighing up to eight tons (Illustrations 2-3). The system of fortifications includes a double wall (a casemate wall) and two gates. The city, which was carefully planned, included an open area near each gate, houses adjacent to the wall and three ritual chambers. The city was destroyed suddenly, shortly after it was established. On the floors of the destroyed structures, thousands of pottery pieces, hundreds of lime and basalt grinding tools, dozens of iron and bronze weapons as well as scores of ritual and artistic items, inscriptions and seals were discovered (Illustration 4).

In the last excavation season in 2013 a broad structure was excavated at the peak of the site. The structure had the following characteristics:

1. Location. The structure is in the middle of the city, at its most prominent spot. You can see the entire city from the building as well as broad swathes of territory from the Mediterranean in the west to the Hebron Hills and Jerusalem to the east.

2. Scope. The structure is 1000 square meters, larger than any other structure in the city by orders of magnitude.

3. Number of Floors. While the regular houses in the city were built from thin walls, this structure has walls which are twice as thick, which means there were a number of floors. The combination of its location at the peak of the site and multiple floors, created a very prominent structure in the city’s landscape and its surroundings, and it can be seen from a few kilometers away.

Another unusual structure is a long and narrow storage facility, where there once stood two rows of pillars (Illustration 6). These structures are typical of the Iron Age and have been found at a number of sites such as Beer Sheva and Hazor. These are storage structures in which agricultural produce was centrally collected, largely in jugs, including wheat kernels, barley, lentils, oil, wine and so on.

The location of the palace and the storage structure indicate a centralized polity, one capable of organizing the construction of a fortified city with administrative and government buildings. It is therefore clear that a royal administrative city was built at Khirbet Qeiyafa.

Economically, one must make note of the extent of commercial activity in which the city’s residents were engaged. We will move from the immediate vicinity of the city outwards: evidence was found of regional trade with the nearby Philistine cities, including high-end pottery (known as “Ashdod Ware”), which apparently contained perfumes, special drinks or medicines (Illustration 7). Scores of basalt tools, which amount to a few hundred kilograms worth of tools, testify to inter-regional trade, with either the Eastern Galilee or Transjordan – areas where basalt is present. Bronze tools attest to trade links with the Arava bronze deposits. International commercial ties are reflected in pottery from Cyprus, alabaster tools and scarabs from Egypt, and tin for the copper industry which apparently came from Anatolia.

Over the years, burnt olive pits were sent for dating at Oxford University. These were examined and dated according to the carbon-14 method to the period between 1020-980 BC, that is the end of the 11th and the beginning of the 10th century BC. According to Biblical chronology, this period is prior to Solomon and fits that of Saul or David. When these results came in the Minimalist and the Imagination approaches suffered a powerful blow, as they could no longer argue that centralized political activity such as city fortifications started only 300 years later in Judah, at the end of the 8th century.

In their attempts to protect the old and now crumbling theories, researchers from the Imaginary School began proposing that the site is not Judahite, but rather a Philistine site, a Canaanite site, or a site built by Saul and belonging to the Northern Kingdom of Israel. The same researcher who proposed that the site is Philistine in 2008 suggested that the site is Canaanite in 2012. One could easily continue in this vein and propose that Khirbet Qeiyafa is Hittite, Perizite, Emorite, Girgashite, Jebbusite or Hivvite (See Joshua 24:11), as far as imagination will take us. The fact that the Minimalists cannot present a single concrete and convincing proposal, rather than numerous proposals which contradict each other, shows that they lack any real arguments.

Who Lived at Qeiyafa?

Today the main debate is solely on the ethnic level: who built and lived at Qeiyafa. In the opinion of the excavation expedition, this is a Judahite site, and this for a variety of reasons:

1. The city plan at Khirbet Qeiyafa is known from another four sites (Tell Nasbeh, Beit Shemesh, Tel Beit Mirsim and Beer Sheva), all of which are in the territory of the Kingdom of Judah.

2. Thousands of animal bones were found at the site, including goats, sheep and cattle. These are direct testimony to the residents’ nutrition and eating habits. No pig bones were found at the site at all. At the Philistine sites of this period, at Gat and Ekron, pig bones could reach as much as 20% of the animal remains at the site. Therefore there was no Philistine population at Qeiyafa.

3. The metal tools at the site are made mostly of iron, as was common in this period at sites in Judah. By contrast, at Canaanite sites and sites of the Northern Kingdom of Israel they continued to use mainly bronze tools.

4. In the three ritual chambers uncovered at Qeiyafa a variety of ritual vessels were found including headstones, altars, libation vessels and temple models. No figurines (small statues) – either human or animal – were found in the chambers. At Philistine, Canaanite and the Northern Kingdom of Israel sites (Hazor, Meggido, Taanach, Jezreel, Rehov), human figurines were excavated, primarily naked female figurines which apparently represent fertility goddesses.

5. 650 jug handles with circular impressions were discovered at Qeiyafa, the impressions apparently constituting a potter’s thumbprint. For 800 years, until the Hellenistic period in fact, it was customary in Judahite administration to mark the handles of storage jugs with a prominent mark. This phenomenon is not known at Canaanite, Philistine or Northern Kingdom of Israel sites.

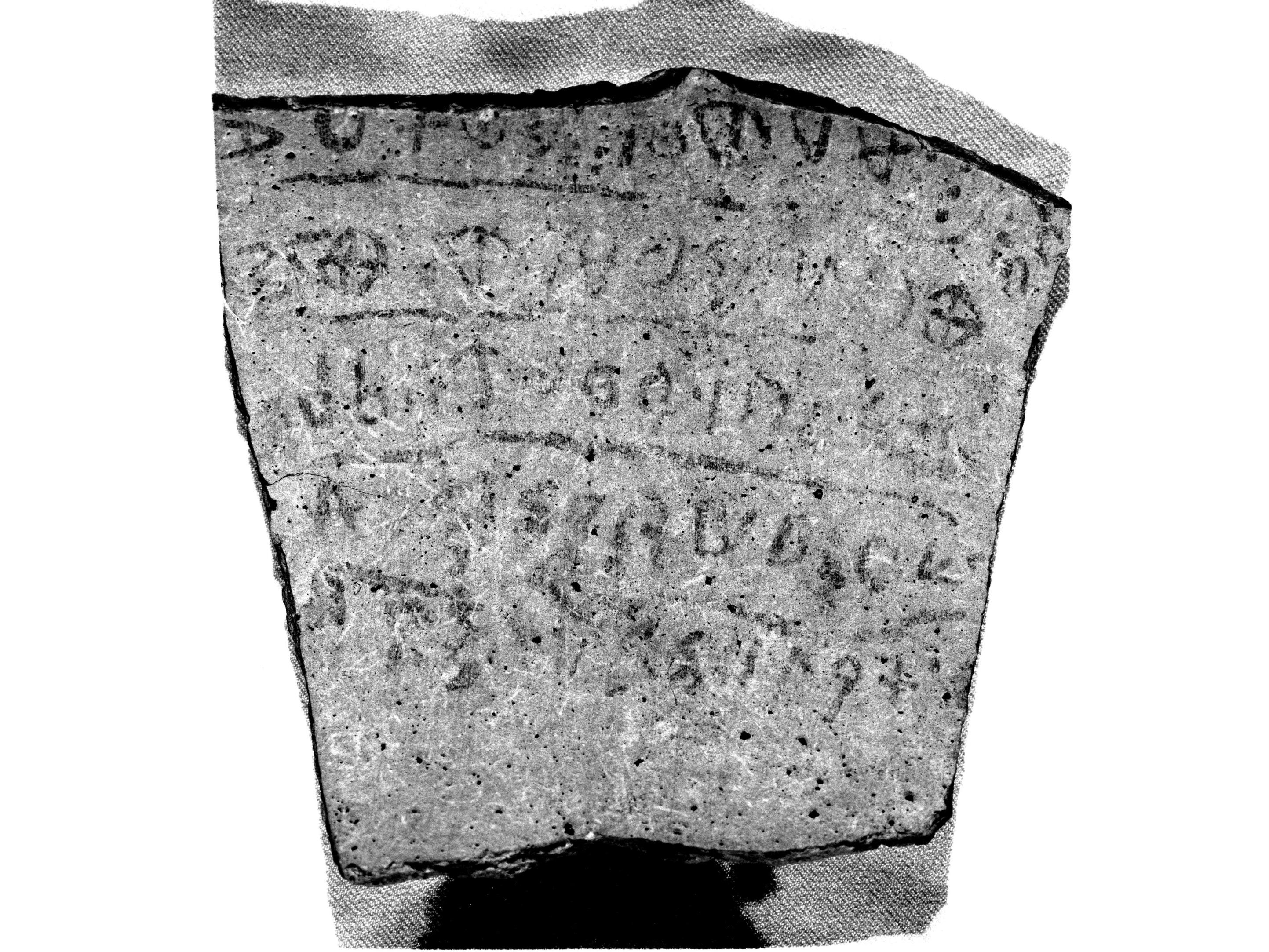

6. The inscription discovered in 2008 contains the expression “al ta’as” (lit. don’t do; Illustration 8). The verbal root a-s-e is known in the Hebrew language and not the Canaanite or Phoenician dialect. An inscription discovered in the Philistine city of Gat includes Greek names, and is not a Semitic language inscription. In general, we should note the impressive number of inscriptions discovered in recent years from the period of the Judahite Kingdom’s genesis: at Khirbet Qeiyafa, Beit Shemesh and Jerusalem. These testify to people capable of reading and writing, who could chronicle historical events and preserve them for generations.

In light of all these aspects: city plans, nutrition, iron tools, ritual, organization of administration and the language, we are of the opinion that Khirbet Qeiyafa is a Judahite site – not Philistine, Canaanite or belonging to the Northern Kingdom of Israel. The site’s ancient name – based on an analysis of the site, its date and the meaning of the name – was in our opinion Biblical Sha’arayim. It turns out that around 1000 BC, a centralized monarchy arose in Judah which was capable of building fortified cities, exacting taxes and conducting extensive trade (Cyprus, Egypt).

We do not know the extent of this kingdom. Did it only control the south of the country or also the north? Current research has no clear data on the matter. However, it is clear that the abundance of new data entirely changes our knowledge of the genesis of the Biblical Kingdom of Judah and attests that the Biblical tradition indeed preserves highly valuable historical information.

Prof. Yossi Garfinkel, Institute of Archaeology, Hebrew University. Extensive discussion of these issues, accompanied by illustrations and photos, can be found in the book “Traces of King David in the Elah Valley” (Hebrew), published by Yediot Aharonot.

The article was translated by Avi Woolf.

To receive updates on new articles in English, join Mida on Facebook or Twitter.

Wonderful article, but I’m biased – I helped fund the dig for the last 7 years. One correction: when discussing trade with Egypt, I believe ‘scarabs’ would be a better translation from the Hebrew than ‘beetles’…

JB Silver