Wondering why Israeli public initiatives take forever or never happen at all? Ask the unelected and unaccountable District Regional Planning Committee.

Mayors are at their mercy, senior ministers send thank you cards, and even the Prime Minister sends a special emissary with flowers and chocolates • Meet the District Regional Planning Committees, a collection of unelected bureaucrats who effectively run the country • Only here can you find people who say things like “Stalin was a politician, not a civil servant”

“I congratulate the district committee on its decision…The plan for a national park at Palmachim was put forth after a tough and protracted struggle…I’m glad to see that this struggle succeeded, and this unique strip of beach at Palmachim will remain open for the enjoyment of all the public.”

The preceding quote is taken from a statement given after the Central District Regional Planning Committee decided to establish a national park in Palmachim Beach. While it sounds like something penned by an environmental activist or a grassroots leader, it was, in fact, released by none other than Interior Minister Gilad Erdan.

Erdan, a minister who supposedly wields the authority to determine planning policy, was reduced to a cheerleader. This is not an accident. By design, our political system routinely requires senior ministers to engage in “touch and protracted struggles”, to court powerful bureaucrats and finally to “congratulate the committee on its decision” to ensure that they don’t fall out of favor in time for the next round of decision-making. Instead of managing his ministry and dictating policy, the elected official is forced to campaign publicly like some sort of student union leader.

Even Netanyahu Grovels

Perhaps it can be dismissed as a trivial matter. It was, after all, only a national park. But the next story should already set off warning sirens. In September 2014, the Jerusalem District Regional Planning Committee convened to discuss a request by IEL, an Israeli energy company, to conduct experimental drills in a site near Beit Shemesh. The drill would determine the feasibility of using the site to produce oil from shale, found deep underground. The project, which had already been dragged through endless amounts of red tape, was in its final stages. It had the potential to transform Israel’s energy sector and some experts had suggested that Israel’s energy reserves matched or even surpassed those of Saudi Arabia. Government officials were already looking forward to Israel’s new international status as an energy exporter, and Prime Minister Binyamin Netanyahu personally supported the initiative.

Unfortunately, transforming a country like Israel into a regional power requires the consent of unelected civil servants. Since the project was of supreme national importance, PM Netanyahu sent his chief economic advisor, Prof. Eugene Kandel, to try and convince the Committee to authorize the plan. In a shocking display of role-reversal, Prof. Kandel found himself begging the head of the Committee to recognize the value of the initiative, since under no circumstances could the Interior Minister (Gidon Sa’ar at the time) order her, his subordinate, to authorize it. A matter of national importance was entirely at the discretion of a civil servant. Of course, the committee’s decision was a foregone conclusion. Buckling under the intense pressure of the green activists and NGOs, the committee rejected the plan by a margin of 13-1.

The District Regional Planning Committees

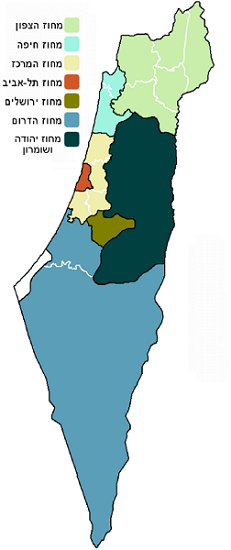

Bloated bureaucracy abounds in Israel, but the most outrageous manifestation of the problem is, without a doubt, the District Regional Planning Committees. The District Committees are made up of unelected civil servants from different ministries. They do not stand for election and they aren’t subject to any sort of public scrutiny. Any mayor – who is, of course, the elected leader of his constituency – who wants to carry out a building project or city-planning initiative has to go through the District Committee in charge of his municipality. Thus, any meaningful decision regarding the physical appearance of our environment is made by a dry committee of civil servants instead of by our elected leaders. Urban renewal projects, roads, cultural sites, open park space, and almost all types of urban/environmental planning are all regulated by unelected bureaucrats. And if you think they’ll automatically rubber-stamp any decision that our leaders push for – you’re wrong.

How did this happen? Upon the foundation of the State and the retreat of the British High Commissioner, the Israeli authorities decided that any law (whether British or Ottoman) that was in force before independence would remain in force unless otherwise stricken from the books. Thus, for example, the residual civil code that was in place until 1984 was the Ottoman Shari’a Codex (!) until the Knesset passed the “Cancellation of Mejelle Law” which finally removed Muslim religious law from civil matters in Israel.

During the Mandate, while the British allowed the “natives” to democratically elect mayors, the law required that all their decisions be approved by District Commissioners, all of whom had to be British officers. After independence, the essence of this system was maintained, with the powers of the High Commissioner and his District Commissioners now spread among the different government offices. The authority to appoint District Commissioners was vested with the Minister of Interior, and the title was changed to “District Director”. But the technocratic title is misleading – the so-called “District Directors” are, in fact, metropolitan mayors who wield immense powers over huge tracts of land.

How Does It Work In The Rest Of The World?

The vast majority of the western world has democratically-elected regional governments, which manage mid-level issues between the central government and the municipalities. In Britain, for example (the country on which our system is based), there are around 90 counties, with an average population of 590,000 people per county. Every four years, the residents of the counties elect their representatives, who in turn are responsible for most of the civil issues of the county.

The official website of the government of the UK explains that county government is responsible for education, transportation, planning, fire safety and rescue, social care, libraries, waste management, and trading standards. Local councils are usually responsible for services like trash collection, recycling, council tax, housing, and planning applications. Put differently, the counties are mini-governments which are empowered to deal with most internal issues of the area.

If the UK isn’t a good example – Israel is, after all, a much smaller country – we’ll present two examples of places which are similar in terms of size and population (8 million inhabitants on roughly 22,000 sq. km): The Netherlands and New Jersey in the United States.

The Netherlands is even more densely populated than Israel. It has a population of 16 million and encompasses only about 30,000 sq. km. In other words, it is about 1.5 times denser than Israel. Like the UK, the Netherlands is divided into regions of about several hundred thousand citizens each. In total, it has 12 regions which are managed by officials who are elected by popular vote every four years.

New Jersey is very similar to Israel in terms of size and population (around 8.7 million residents and encompassing roughly 22,000 sq. km of land). It is also divided into counties (21) which are managed by politicians who rotate gradually (meaning not every seat is up for election every time) every three years. Like the counties of Britain, the counties of New Jersey manage the internal civil affairs in matters related to education, welfare, police, transportation and infrastructure, and economic development.

But even if it is more democratic, is it really more effective? To examine that question would be outside the scope of this piece, but one anecdote could serve as a yardstick. In New Jersey there are 61,000 km of paved roads, of which 93% are managed by the counties. Only 7% of the total paved roads in New Jersey are managed by the state or the federal government. In contrast, Israel only has 20,000 km of roads, courtesy of the centralized Ministry of Transportation.

One could argue that here we don’t need it. In any case we have a politicized society fragmented by a complicated multi-party system. Do we really need more politics? But this is precisely why we need to democratize regional government – if every metropolitan area knows that it can run its own affairs, the makeup of the governing coalition in the Knesset will become less important to our daily lives as citizens.

Democracy for Show

Nevertheless, who can we elect? Israeli citizens go to the polls for only three things – party list in Knesset, party list in municipal government, and mayor. That’s it. Every other decision is made for us by government committees. This situation creates the illusion that we are free to democratically choose what our environment will look like, when in reality, so much of what affects us is decided in tucked-away back offices. The bureaucrats who decide for us still operate the way the British did more than 60 years ago. As far as they are concerned, the stupid natives can’t be allowed to decide for themselves. If we give them the freedom to choose, they won’t know what to do with it.

I recently had a discussion with a senior bureaucrat in one of the district committees. We were speaking about another matter entirely, but I decided to ask her what she thought of Israel’s unique situation.

Bureaucrat: It’s a very good thing we have our system.

EK: Why is it very good?

Bureaucrat: We’re better off with professional civil servants making these types of decisions.

EK: But in the rest of the democratic world these positions are filled by elected politicians.

Bureaucrat: It would be terrible if we had that here. It would lead to politicization.

EK: Isn’t politics good? It would promote transparency and good governance – and at the end of the day, the people could choose what they want.

Bureaucrat: Actually, only civil servants can prevent corruption.

EK: What you’re saying sounds rather anti-democratic.

Bureaucrat: Oh, please. Democracy is government on behalf of the people, right? The professionals act without any prejudice and only for the good of the people. Politicians will only introduce corruption into the system.

EK: So what, then? Maybe we should bring Stalin here. He also governed “on behalf” of his people.

At this point she looked at me and gave me, with a completely straight face, the most appalling answer she could have possibly given.

Bureaucrat: Stalin was a politician, not a civil servant.

At that point it was ever-more clear to me that we have a real problem. As far as our regional authorities go, we live in a sort of dictatorship that doesn’t at all resemble the enlightened international community to which we aspire to belong. Fortunately, there is a fairly simple solution.

How to Fix the Problem

This is what we need to do: The next Interior Minister, who will assume office following the 2015 general election, needs to cancel the outrageous position of District Director and establish district councils which will be made up of elected leaders. Elections could be held every 5 years, either on the day of the municipal elections or 2.5 years later (so as to allow people to react to changes) and it would hardly cost the taxpayer any extra money. The elected council-members would receive a full salary, at the expense of the current civil-servants who are currently running the districts from within the various civil ministries (interior, transportation, environmental protection, etc.), so the district councils would not even come at any extra cost to the public.

Afterwards, all the relevant civil ministries would be required to delegate some of their powers to the new district councils. As already noted, the district councils will better serve their constituencies, be subject to far more transparency and criticism, and know that if they don’t take care of the needs of their constituents – they’re going to be voted out of office. The districts will be charged with developing the metropolitan areas of the State without unnecessary red tape, and the central government in Jerusalem will be free to deal with national issues such as the economy, security, foreign affairs, and the court system.

This new reality would relieve senior ministers of the terrible strain of the current system, which forces them to deal with trivial matters rather than the major strategic issues. In turn, the citizens of the State will be free to manage their affairs by themselves, without the interference of endless bureaucrats and civil servants.

To receive updates on new articles in English, join Mida on Facebook or Twitter or join our mailing list.