Contrary to post-elections cheers and jeers, Israel’s public remains staunchly pragmatic and non-ideological. Here’s how the right can work with that.

Many right-wingers are ecstatic, thinking the election proves that the majority of Israel is “right wing” and on their side · Well, not exactly. In fact, not even close · An honest look at Israel’s political map—and how to swing it our way

Binyamin Netanyahu’s sweeping victory in recent elections have created the impression that “the majority of Israel is right wing” and that Netanyahu now has the legitimacy, if not the outright obligation, to push an overtly right-wing agenda, freed of commitments to the political center or left. Most of those who push this line are in the bloc to Likud’s right—a bloc which has been steadily shrinking over the past two elections—and they want Likud to annex parts of Judea and Samaria, fight the left-wing media and academia, solve the loyalty problem of Israeli Arabs once and for all, and declare all-out war on the Supreme Court.

This demand ignores both the actual electoral results and the general will of the majority of the population. It also takes no heed of the task of a country’s political leadership.

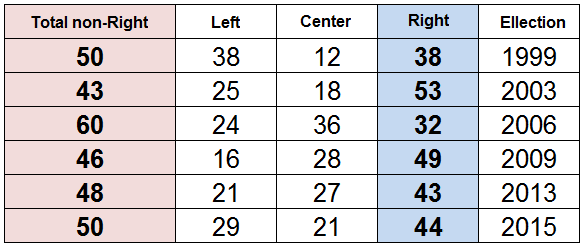

First, we need to figure out what the “people” wants. When we examine the election results of the past ten years, it’s easy to see that the “people” is far from right-wing. Indeed, the center-left bloc has generally been bigger than the explicitly right bloc, in the recent elections included. The 2003 elections are thus an anomaly in this regard, perhaps due to the combination of the Second Intifada and the leadership of Sharon.

Most of the people are not “right” or left”. Neither ideological side has attained a clear majority, and both sides are dependent on votes and parties from the center. In fact, a large part of both the right and left blocs tend towards the center and are non-ideological in general, but vote for one of the two big parties for various reasons.

Contrary to their often harsh partisan public image, Likud and Labor are both large and pragmatic parties, which despite the differences between them on a variety of issues are open to compromises for the common good. This is why both Meretz and Jewish Home would have difficulty sitting in a National Unity Government, while Likud and Labor have no problem making noises in that direction.

The Poll Paradox: Pro-Peace, Anti-Left

The Israeli public’s generally centrist positions are revealed not just by election results but also general opinion surveys.

Every so often, both right wing and left wing organizations publish opinion polls on peace and evacuation of settlements. The polls from both sides generally reach similar results: “the majority” supports them. The Left argues that “76% of the public are in favor of the arab Peace Plan” while the Right surprisingly concludes that “74% oppose the establishment of a Palestinian state.”

Ostensibly, these two results contradict each other—but only ostensibly. A closer look shows that the two stats complement each other. The best demonstration of this is a Haaretz peace poll which was presented last July at its peace conference. According to the poll’s headline, 60% of the public support establishing a Palestinian state. But when asked more detailed questions, that support falls drastically. For instance, when asked if they would support an agreement which included “establishing a Palestinian state with the 1967 borders with border adjustments, most of the settlers annexed to Israel, the division of Jerusalem and no return of refugees to Israel,” the support drops to 35%, with 58% responding in the negative.

So a clear majority of the Israeli public wants peace and is willing to evacuate territory and some settlements to do so. But when faced with a concrete program based on present Palestinian demands, the response is a resounding “no.”

A Walla poll from a year ago reveals similar tendencies. “76% of the public favor the Arab peace plan,” shouted the headline, but the fine print showed that “77% said that in their opinion, the Palestinians are not interested” and 73.9% argue that they will support an agreement in which “the Palestinian refugees will not have a Right of Return into the territory of the State of Israel.” So, the majority is in favor of territorial concessions, in contrast to the hard right. But they are also a majority with common sense, and they are not interested in the extreme and dangerous deal offered by the Palestinians and the hard left.

The ultimate proof of this bifurcation is the $64,000 question: a return to the ’67 borders. In exchange for “the end of the conflict, full relations with Arab and Islamic countries and opening up the Israeli export market to 300 million people,” the public is 76% in favor of withdrawing to the Green Line. But does the public think this realistic? Will they vote for a candidate whose stated purpose is to achieve this? The most reliable poll around—Knesset elections—shows that they don’t.

The pollsters and those who order the polls deceive the country with misleading headlines. But there is a real lesson to be learned here: most of the Israeli public is not ideologically right wing. The consideration of Greater Israel, separation from Gentiles and Jewish identity, plays a part in the political considerations of only a small part of the public. The rest are pragmatic: they are willing to give up important and large parts of the Land of Israel to the Arabs—in theory. But they are far from naïve, and they demand real and lasting guarantees and achievements in exchange for such a price. This position finds expression among much of the Likud supporting public and some Labor supporters.

An overwhelming majority for leaving Judea and Samaria

When we understand this, it’s easy to see why the Disengagement Plan was so popular: the plan purported to address Israel’s security needs and didn’t try to market fantasies of peace. “We’re here and they’re there,” a pragmatic and convenient solution to the Palestinian problem. The public loved it. How do we know? Simple: in the 2006 elections, but a year after the Disengagement, Olmert claimed that he would work toward a “Realignment Plan,” in which Israel would unilaterally withdraw form 97% of Judea and Samaria. It turned out there was no “national trauma” from the Disengagement in these elections, and Kadima won 29 Knesset seats. Labor won 19. Netanyahu and the right-wing “rebels” barely scratched 12.

So what does the “people” want? It’s simple: security, prosperity and a high standard of living. The masses love the Land of Israel, of course, but they do not see it as a value which supersedes all others. They’re also not interested in individual freedom or the rest of the right wing-conservative agenda. They are only interested in results. If holding onto Greater Israel helps the security of Israel, they’re for it. If individual freedom and economic growth lead to prosperity, then they’re right wingers. If they are convinced they will get what they want with the opposite—withdrawals, regulation and market barriers—then then they will be left wingers.

That’s the situation, like it or not. Most of the public is not “ideological,” it’s pragmatic. It admires moderation and restraint, and likes to see progress which does not bind them to any hard and fast position.

So What Is To Be Done?

All this requires us to gain a new understanding of the function of political leadership. One of the common arguments of the ideological right is that the government needs to conduct revolutions within the system. We need to “fight the public sector unions” and conduct wholesale reforms in the justice system, the defense and foreign establishments, and so on. Naturally, those who advance such ideas tend to be extremely critical, seeing anything which falls short of their demands as “surrender” and people not interested in going that far as “leftist.”

This is wrong on two counts. First, as we saw above, most of the public is not extreme and is not interested in wrecking and revamping the whole system. A government that veers too sharply—even if perfectly legally and democratically—could end up scoring an own goal and risk losing the next election.

Second, there’s a fundamental misunderstanding here of the function of government. We need to distinguish between two types of right-wing. There’s the ideological right wing, which aims to change things right away according to its ideological agenda, and there’s the conservative right wing, whose purpose is to preserve present gains and aim to change matters in a slow, measured manner without causing too much damage to the existing structure.

The ideological right sees the government as a tool for carrying out its ideological agenda and sees any failure to do so as a complete failure. The conservative right understands that governmance involves an ongoing responsibility to deal with a changing reality, with the main goal being to preserve the institutions of the past alongside creating frameworks which allow prosperity.

The ideological right fights to change the foreign status quo, declare war on the media and academic elites, and strengthen the religious-cultural identity of the state through government organs. The more conservative right, on the other hand, will divert most of its attention to ensure the state’s security, increase its trade and see to more basic elements of society such as education, particularly in the sciences and technology.

It’s important to stress that there are no disputes of principle between the ideological and conservative right. Both groups can agree on the long term goals regarding the desired shape of Israeli government and society, and in many cases both sides will also agree on how to get there. In fact, the present author holds many positions which many on the ideological right would consider too extreme, both in the political and economic fields. The differences are thus far more in the “how” as opposed to the “what”, and the appropriate relation between the “is” and the “ought”.

Most of the actions of a conservative right-wing government involve inaction, sometimes under enormous pressure. The conservative leader stands firm against international pressure, sometimes using all kinds of non-ideological methods to head that pressure off. He holds off on increasing regulation at the behest of large corporations aiming to kill their smaller competitors. He ignores mass-based populist movements which aim to increase government spending, price fixing or the subsidizing of basic goods. Most importantly, he works tirelessly to promote conditions that will encourage investment and economic growth.

These are far from politically heroic acts, of the kind that earn a front page headline or become the first item on the nightly news. To the contrary, because of the pragmatic nature of his steps, the conservative leader is often blasted by criticism from all ends of the political spectrum. One side argues that his policy is “apologetic” and hesitant, others that he is not paying attention to the wishes of “the people” or “the world”. When you add to this the fact that the conservative leader usually does not bow to the interests of various pressure groups, the result is a very unpopular leader. Even though the raw data show that he accomplished a list of very impressive achievements (as Ori Katz described at length), the conservative leader is attacked precisely in those areas in which he succeeded.

This description, even though it’s true to a large extent for the Likud Government of the past few years (with a few exceptions, like the populist last term), is true also to the members of the ideological right who sat in the government at that time. Governmental responsibility is conservative by nature, and one needs to be an extreme radical or populist not to realize this. Responsibility can teach power and arrogance but also moderation and humility. History is on the side of the latter.

Conservative Changes

This doesn’t mean that we shouldn’t be making any changes at all. It’s just that those changes should be measured and moderate with a view to effecting long term transformations. Indeed, the less media buzz they cause—the better.

Here’s a list of a few possible ones.

The Legal System: there’s been a need for a reform of the Israeli Bar Association for a few years now. The IBA, a statutory legal institution which sends two representatives to the Judicial Selection Committee, has a great deal of power in the legal system, and what happens there has strategic consequences. The convoluted structure of the IBA, which includes a national council and district councils as well as other adjacent bodies, has caused many problems, paralyzing the IBA’s work and wasting a lot of resources, sometimes in contravention of the law. Mida listed a few of these problems in the past. An official Commission of Inquiry chaired by Justice Procaccia inquired into the matter, and submitted a report recommending abolishing the district councils in the IBA. These recommendations were promoted by then-Justice Minister Tzipi Livni, but the legislation was stopped because of elections.

Why is all this important? Simple: the move increases democracy within the IBA and removes the outsized power of small districts and ideological pressure groups, returning the power to the broad public of lawyers, which like the general population has become increasingly though not exclusively conservative-right-wing. It’s no surprise that lawyers with ties to the New Israel Fund strongly oppose the move.

The ultimate result of the move is increasing the public’s say in the selection of judges. It’s a small, indirect move, and it does not reflect the entire “public”. Indeed, it still leaves Israel far behind most other democracies in this regard. But such a move—which enjoys a political consensus—could positively affect the legal system in a stable and long-lasting way, much more than more media-grabbing struggles or fire-eating speeches in the Knesset hall.

Economics: here, too, a little can go a long way. Advancing the reform of the Standards Authority, which is already underway (and former Economy Minister Bennet deserves the appropriate credit for this); a stable and moderate reduction in taxes, removing import barriers, lowering customs duties on various items and continuing the policy of attracting investment—all of these steps would have a great effect on the economy, especially economic freedom and growth.

Those who want to go further could change some of the burdensome and restrictive labor laws, place some restrictions on the Antitrust Authority, and maybe even let international banks operate in Israel—an easier and safer method than try to “encourage” competition among local banks. Every citizen would feel the difference at the end of each month, even if they don’t exactly understand how (don’t worry, none of us do).

Education: it’s hard to change the state educational system. It is a huge, convoluted and sclerotic behemoth which is paralyzed thanks to the extremely restrictive employment rules. Despite this, changes can still be made here as well, through the simple method of getting out of the way. The way to improve education is through encouraging competition among educational institutions, and competition needs freedom like we need oxygen.

Because of the fixed nature of the system, the Education Minister can’t play a lot with the budget of his Ministry. But he can get out of the way of others, especially by stopping the war against private education, excellence programs and parents’ payments for extra-curricular activities. Removing the barriers to establishing private schools—including those funded entirely through private funds—can also work wonders. Alongside the frozen state system, a variety of private schools of all kinds would spring up, forcing the state system itself to improve and become more efficient.

Within the state system, parents should be allowed to compete for schools outside of the limiting registration areas. In addition, small changes can be made in the employment conditions of new teachers and increasing the responsibility and authority of school principals. All these would lead to a tangible and significant change over the next few years, not all of which are subjects of controversy. Even strident opponents of privatization like ex-Education Minister Piron has been known as advocating the strengthening of principals.

We could list many such steps in other areas, but the principle is clear: conservative leadership can do a lot, while maintaining a generally stable and functioning government apparatus. Many small changes can effect big changes. This is what we would like to see.

We hope that four years from now, when elections come around and TV journalists ask citizens what Netanyahu did for them, they’ll have a hard time pointing to anything big and specific. The success of the right wing is not measured in headlines and slogans. It is measured in growth tables, mass sale of smartphones, new cars and consumer goods, satisfaction of citizens (8th in the world), and yes—Knesset elections. This is the test of the right. We leave “changing the world” and revolution to our opponents.

English translation by Avi Woolf.

To receive updates on new articles in English, join Mida on Facebook or Twitter or join our mailing list.