Contrary to common perception, the settlement movement was and remains a national project, not a sectorial one.

Religious Zionists are seen both by themselves and the left as the sole representatives of the settler movement · But the actual history of the settler movement, as well as the voting patterns and demographic makeup of settlements today, tell an entirely different story · How a truly national project became the story of a single sector – to its detriment

The Religious Zionist community in Israel often claims the settlement movement in Judea and Samaria as its crowning achievement. Indeed, the movement has been so successful, that it seems to them a vindication of the Religious Zionist stream itself, proof that the skull-capped pioneers are truly the heirs to their kibbutz predecessors.

There is much truth in this belief, and it would be no exaggeration to say that the settlement of Judea and Samaria was the main contribution of Religious Zionists to the state. In the 1970s and 1980s, dozens of settlements were established throughout the region by Gush Emunim and its settlement company ‘Amana’, and it’s hard to imagine the present Jewish map of Judea and Samaria without their contribution. The idea that a settler is by definition a Religious Zionist is an accepted trope throughout Israel and the world.

This trope serves both Religious Zionist settlers and their enemies. Rabbis and spokespeople for Religious Zionism constantly emphasize the contribution of their community to settlement, the state (and eventual Divine Redemption), and the left finds it convenient to tag everyone across the Green Line as a wide-eyed messianic lunatic.

But this picture is greatly exaggerated, with a few kernels of truth used to prop up an untenable myth. While the contribution and presence of Religious Zionists among settlers is undeniable, their part in both is smaller than many assume it to be.

A Prominent Minority – But A Minority Nonetheless

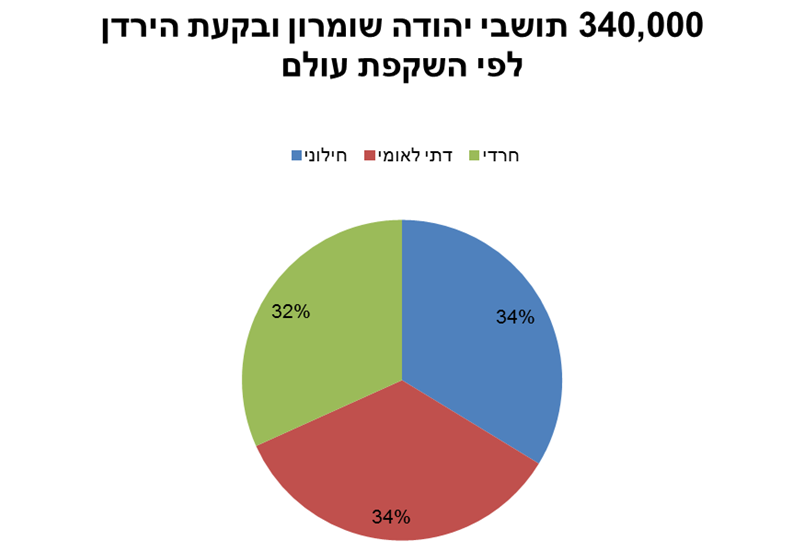

In 2013, the Yesha Council Research Department (full disclosure: I worked there at the time) published a demographic breakdown of settlements in Judea and Samaria according to worldview. The data, collected both from regional councils and individual settlements, showed that only a third of the residents were Religious Zionists. The rest—two out of three settlers—were either Haredi or Secular.

Of particular interest was the demographic breakdown based on type of settlement. In urban settlements, a majority of residents were not Religious Zionist: of 150,000 city dwellers across the Green Line, 62% were identified as Haredim, 29% as Secular, and just 9% as Religious Zionist. By contrast, in the local councils representing small settlements, 62% were Religious Zionist, 31% were secular and just 7% Haredi. Among the 80,000 residents of local councils—medium size towns without acceptance committees—45% were identified as Religious Zionist, 46% Secular and 9% Haredi.

So of 340,000 settlers, only 110,000 belong to the Religious Zionist sector, and most of these live in small, largely homogeneous towns which maintain this state of affairs through acceptance committees.

This breakdown is also expressed at the polls. An analysis of voting patterns shows that supporters of the Religious Zionist party Jewish Home are a minority among settlers. Even in 2013, when the Jewish Home party reached its peak, just 28% voted for them, while 21% voted Likud and 27% for Haredi parties.

These numbers remain consistent when we check other elections results in Judea and Samaria: the Likud, Jewish Home and Haredi parties each get about 25-30 percent of the settler vote.

| 2015 | 2013 | 2009 | |

| Jewish Home | 25% | 28% | 28% |

| Likud | 24% | 21% | 26% |

| Haredi Parties | 24% | 27% | 25% |

| Yahad/Otzma | 10% | 7% |

A History of Non-Sectorial Settlement

The role of Religious Zionists in the settlement movement is also more modest from an historical point of view. Already after the Six Day War, a series of strategic settlements were established based on the Alon Plan. In these years, settlements were established in the Jordan Valley, the Judean Desert, and the area around Jerusalem. In parallel, there was a return to Jewish areas which had been abandoned before or during the 1948 War of Independence such as Gush Etzion and Kiryat Arba, a return which also involved Religious Zionists.

In fact, Gush Emunim was established after there were already many settlements on the ground and after the large urban settlements—responsible for a large portion of the settler population—were already established. Gush Emunim and Amana were mostly responsible for the small, socially selective Religious Zionist settlements mentioned above.

In 1975, when Gush Emunim established its first settlement—Ofra—there were already 22 settlements in Judea and Samaria, including two cities—Maaleh Edumim and Kiryat Arba—as well as the beginnings of the city of Ariel, which began in earnest in 1978. About 80,000 residents, some of them National Religious, live in these settlements.

In the years afterward, and especially after the political upheaval of 1977, there was a flowering of settlement in Judea and Samaria. Gush Emunim and other Religious Zionist organizations founded 58 settlements now containing 100,000 residents. But we need to remember that they were not alone. Other movements and government initiatives founded another 32 non-sectorial settlements, today containing 88,000 residents, as well as the Haredi cities of Modiin Ilit and Beitar Ilit, today containing 105,000 residents combined.

The Historical Alliance

No-one doubts that Religious Zionists played a large part in the settlement movement and that they are worthy of great praise for this. But we need to keep the bigger picture in mind and fit the image to the facts and not the other way around. As a truly national project, various populations took part in the settlement movement, and most of those who live in Judea and Samaria live in settlements and towns established on government initiative or at least outside the Gush Emunim settlements.

Religious Zionists leaders who founded non-sectorial settlements understood reality, realizing that the settlement project must be a national, not a sectorial affair. They didn’t say that secular Jews wouldn’t come. Instead, they built settlements open to all—and they came, so much so that Religious Zionists are a minority across the Green Line. The story of settlement in Judea and Samaria is one of a national, joint effort of Religious Zionists, secular right-wingers and many Haredi Jews besides. But something happened along the way. The focus on narrow sectorial interests turned a national project into one which is identified solely with one sector. This is an historical error of the first magnitude, a misrepresentation of the facts and a political blunder.

The fate of the settlements is largely dependent on them being seen for what they truly are: a national, multi-sectorial effort. The efforts of Religious Zionists to market themselves as the sole or majority population in the settlements is harmful to this critical point, playing in the hands of left-wing politicians and media members. It’s past time Religious Zionists realize this.

English translation by Avi Woolf.

To receive updates on new articles in English, join Mida on Facebook or Twitter or join our mailing list.