We present the new Justice MInister with a serious challenge: rolling back the Attorney General’s unilateral seizure of authority.

A new study shows that Israel’s Attorney General is far more powerful than his colleagues in the most advanced western countries · Meanwhile, he does not even give the government proper representation in the courthouse · Dr. Aviad Bakshi, in an eye-opening interview, talks about how Israel has become a kind of “enlightened tyranny”

A new study has recently been published by Dr. Aviad Bakshi of the Kohelet Forum [see here for the full study (Hebrew)] which aims to examine the present state of affairs in Israel, where it seems that the legal bureaucracy has effectively taken over the reins of government.

“There’s the classical model of separation of powers, of which I am a devoted fan,” Bakshi emphasizes, “wherein there needs to be an authority that states where the line is, where the law has been broken. The authority to do this is the judiciary – it is authorized to interpret the law and issue injunctions against the government. That’s how it’s supposed to be, and that’s what happens in Israeli jurisprudence. I may have a problem with the degree of activism with which they issue the injunctions, but their very authority to do so is not in dispute.”

But that brings up the question of the Attorney General [in Hebrew, “Legal Adviser to the Government” – AW] and his job—is it right that he can issue injunctions and force his opinion on the government?

“Normally, if we take the financial area for instance, an adviser is meant to advise and explain the various legal options to his client. If for some reason the client thinks his adviser is wrong, which is certainly possible, in the end he has the right to decide based on his own judgment and the courts are responsible for laying down the law if it is actually broken.”

Here we should note that Bakshi’s study does not deal with the question of separating the Attorney General’s two powers—that of legal advisor to the government and head of the State Prosecution—but only on the issue of advice at the administrative level. The central question is this:

Is the Attorney General’s advice merely advice, or is it legally binding?

Ever since the 1990s, it has been commonly accepted in Israeli legal circles that the opinion of the Attorney General is completely legally binding on elected representatives. “The fundamental dispute,” Bakshi explains, “is who is the client of the Attorney General: the government or someone else? The position of the supporters of the status quo is that the Attorney General’s client is not the government but the general public. But then you need to ask two questions: 1. How do you know what the public wants? 2. Who represents the government, then?”

According to Bakshi, the job of the Attorney General is to be the government’s lawyer. “Just as everyone has the right to be represented by an attorney, so too does the government. I work on the assumption that the government does not want to break any law. But even if we were more cynical and assume that it does, I don’t think it wants to be humiliated in court. At the end of the day, in most cases, it will listen to the Attorney General. But there are exceptional cases where it may choose a different legal approach, which is its right so long as the court has not ruled otherwise.”

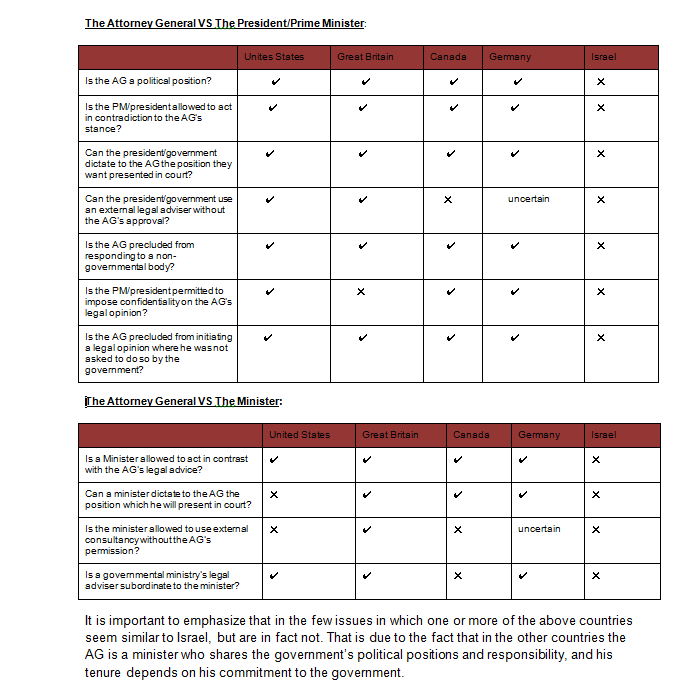

In his study, Bakshi examines the role of the Attorney General in four Western countries: the United States, Britain, Canada and Germany. In all of them, the Attorney General is effectively the Justice Minister—a political appointment whose term begins and ends with the elected government. There are additional major differences: in every country under examination, the government is allowed to act against the Attorney General’s advice, unlike in Israel where it can’t. Furthermore—and again unlike Israel—the Attorney General does not have the right in those countries to present a position I court which differs from that of the government. What about legal opinions? Are they solicited by the government or the public? Once again, in the four countries under examination, the Attorney General only provides opinions upon the government’s request, unlike Israel where he can do so unsolicited.

This last point even led to an interesting story during the study itself: “This fact led to methodological problems. When we tried to learn various details from the German Ministry of Justice, they told us, “Excuse me, we don’t work for you. We only answer inquiries from the government.” We sent another request via a German citizen and once again we got the same answer: we are not lawyers of citizens, but of the government so we won’t answer.”

Another question which came up was the confidentiality of legal opinions. While the legal opinions of the Attorney General and his deputies are often plastered on the front page, “in Germany, for instance, all the legal opinions are confidential, which makes the question of whether they are obligatory moot. There is no outside authority which can examine them.” Thus, the legal opinion cannot be used as a political bludgeon through the media.

“In Germany, there is attorney-client privilege between the Attorney General and the government,” Bakshi explains. “In other countries, there are cases where opinions are made public, but if for some reason the President or the government insists on keeping it confidential, they have the right to do so. They run the shop. The conclusion is clear: in all these Western, advanced democracies, the Attorney General is the government’s lawyer.”

The Jurists Seize Power—and the Elected Government is Silent

The activism of the Attorney General began in earnest during the appeal to fire Deputy Minister Rafael Pinhasi in 1993. After then State Attorney Dorit Beinish argued in the name of Prime Minister Rabin that the law does not require firing Pinhasi, then under criminal indictment, Beinish then moved against her own client. In one of the most influential paragraphs written in his storied career, Justice Barak stated that the Attorney General, as “the authorized interpreter of the law before the Executive Branch”, is not in any way obligated to defend the policy of the Prime Minister:

There are two fundamental rules in this matter. The first is that the opinion of the Attorney General on a legal question reflects, as far as the government is concerned, the existing legal situation; the second, the representation of the state and the offices of government is entrusted to the Attorney General… therefore, if in the opinion of the Attorney General, the governmental authority is not acting within the law, the Attorney General is permitted to inform the court that he will not defend the authority’s action.

As Professor Daniel Friedman explained in his book The Sword and the Purse (Hebrew), not only is Barak’s verdict not based on any existing constitutional tradition, it also contradicts a cabinet decision which accepted the conclusions of a special commission headed by Chief Justice Agranat in 1962, which instructs precisely the opposite. In the wake of this controversial ruling, the Attorney General went from being an advisor subject to the government to an advisor to which the government is subject.

A second aspect of this new authority is that not only does the Attorney General force his now-binding opinion on the government, but he can also dictate the position he will take in his client’s name (i.e., the government) at court.

How did we get from the Pinhasi case to such an absurd situation, which many call the ‘rule of the lawyers’? Is this solely the courts’ doing or are the various governments also responsible?

“Like any process, it started in stages: at first, when a dispute arose, the Attorney General insisted his opinion be brought to a cabinet vote. Later on, Attorney Generals made use of court statements in the Pinhasi case, and expanded it into a wholesale rule of ‘you have to listen to me’. In other words, we have a legal body which determines the limits of its own power. It’s true that the courts gave some support to this, but the transformation of this single statement into a wholesale takeover of authority was in the end the work of the Justice Ministry. I think it has seeped in at all levels—not just the Attorney General. For instance, in this term it’s clear that the Deputy Attorney Generals are far more enthusiastic in issuing incredibly activist opinions.”

“Regarding the government, I think there is a combination of a few things: first, the government is also worthy of a degree of criticism. In some cases, they find it convenient that the Attorney General serves as their sort of legal bulletproof vest. Second, in many other cases, governments wanted to do something else, but they were afraid to confront the Attorney General. Why? Because of the public image. The lawyers are seen as the “good guys” and the politicians as the “bad guys”. The politicians know this and adapt their actions and image accordingly. Third, there really are many cases where public representatives don’t know the law well enough, don’t know what their rights are and how the system’s actually supposed to work.”

“The result is they don’t have a legal advisor to let them know that the Attorney General’s legal opinion is overstepping its bounds. This is an exploitation of the system by the Attorney General, where instead of being an advisor to the government and expanding their range of options to the maximum possible, he’s the one who limits that range—it’s a classic “Representative’s Dilemma.” This in a situation where the client does not have the option of getting a second opinion from which he learns the problems of the first.”

“Finally, there is the argument, which I can’t firmly establish but which has been brought up repeatedly by very senior people—such as former Justice Ministers Daniel Friedman, Yaakov Ne’eman, and Hayyim Ramon—that the combination of the General Prosecution and the Attorney General’s Office leads many elected representatives to fear confronting the Attorney General on opinions he claims are “binding”, for fear of later being punished in criminal matters.”

There’s a simple way to solve the problem: hire an outside advisor or fire the Attorney General. Why hasn’t this happened?

“Here, too, the Attorney General established that one can make use of an outside advisor—but only with his approval. In general, he approves it more when there are work considerations: when there’s a certain kind of civilian professional specialty required in a case in which the state is involved, then the state can hire private firms under a whole host of limitations. But bottom line: the Attorney General’s position is that a minister interested in outside representation, because he doesn’t find the Attorney General’s position convenient, is not allowed.”

“Who says the Attorney General is Immune from Populism?”

Two Commissions of Inquiry have dealt with this issue over the years: one in the early 1960s, headed by Supreme Court President Agranat, and one in the late 1990s headed by retired Chief Justice Shamgar. “Bottom line, both Commissions determined that the last word needs to be in the hands of the government,” Bakshi insists on reminding us. “True, they declared that it is appropriate that the government listen to the Attorney General’s opinion as the “guiding” one, but in the end it may decide as it sees fit so long as the court did not decide otherwise.”

“There’s another point I’d like to emphasize, and that is the correlation between judicial activism and the activism of the Attorney General. If we lived in an environment where the court only examined the technical connection between the language of the law and reality, I wouldn’t be too concerned. That’s a situation where the elected representative either didn’t know the law or ignored it. But in a world in which almost every legal question is put to a test of “reasonableness”—is it reasonable to work with the Settlement Unit (of the World Zionist Organization), is it reasonable to appoint a new Police Chief during an election—in a situation where the Attorney General can effectively force policy on the government, that’s very problematic.”

Another problem is the separation between authority and responsibility: “This separation leads to a situation where the public can’t expect results from anyone. The minister claims he wants to carry out a policy but the Attorney General won’t let him. The Attorney General meanwhile is certainly not the address, because he doesn’t administer policy.”

You’re arguing that the Attorney General needs to represent only the government. So who protects the public?

“When a member of the public is harmed by the state, he can go to the courts. More than that, Israel allows a very broad right of standing, which allows those who haven’t been harmed to sue [for others]. If there’s a criminal violation of the law, then one can certainly appeal to the Attorney General as General Prosecutor. Then all these tools are around. So what do you do if you’re not comfortable with the fact that the government is involved in building settlements? So here’s a solution: try to compete in democratic elections and change what you think needs changing. That’s the arena in which policy is altered. The current situation where an unelected official decides policy harms democracy at its most basic level.”

Bakshi also argues that the current situation harms the governance of the country. “There needs to be one boss whose decisions are carried out. Lack of action means anarchy, and that’s the worst possible scenario. In the existing situation, government representatives try to get things done and the legal advisors [the Attorney General and legal advisors of ministries – AW] stop them in their tracks. For instance, Netanyahu was elected in 2009 and he wanted to promote the ‘Pergola Reform’ and remove some of the regulatory barriers involved in planning and construction. They even passed a law which prevents too many committees from being involved in these processes. The legal advisors showed up and through legal acrobatics restored the status quo. In some cases they can even delay a decision by doing nothing—they just delay the implementation of a decision.”

“Another aspect of this point is the court. It grants injunctions against the government—one can support these, one can oppose them, but those are the rules of the game. That is, one branch acts and the other responds. But we have a situation where the court decides but doesn’t bear responsibility. We have here an activist branch that prevents any action but also response on the part of the other two branches. It’s a kind of masquerade ball—a legal position is forced on the executive branch which is then also presented as its original position. This denies the branch due process and leads to a situation where its lawyer becomes its judge.”

You’re making very serious accusations against the existing stand of the Justice Ministry. They argue that all they’re doing is protecting the rule of law and fighting corruption.

“Of course the state needs to be based on the rule of law, prevent corruption and check unlimited power. That’s the basis of the idea that the law needs to be enforced on the government. I identify entirely with that approach, and it’s the same in the rest of the world. But there, it’s the job of the courts to ensure this. In Israel they decided it’s not enough. The Jews are ostensibly too clever (but only in the executive and legislative branches) and therefore we need more significant steps. Supporters of judicial activism see the Attorney General as a forward bastion within the executive branch. They’ve created a situation of legal stringencies upon stringencies, and it’s gone out of all proportion. Tzvi Hauser [Israel’s Cabinet Secretary from 2009-2013] said as much in an interview, that in order to increase legal compliance from 98% to 99%, we’ve paid a very heavy price in all the other arenas.”

“The second aspect of this mistake is the assumption that the elected representatives are “the usual suspects” and they need to be watched. But who will watch the watchers? Populist decisions can’t be made by lawyers? They’re immune? They’re often referred to as the “responsible adult”. Hang on, who decided you’re the responsible adult? Who gave you that authority? If I’m a doctor, does that mean I can force any experimental treatment I feel like on my patient, or do I respect his being an autonomous being with the right to choose? There’s a situation here of an “enlightened tyranny”—someone who really cares about the state, but who says his opinion is better than others? It’s the ABCs of democracy.”

So, how do we fix the situation? According to how you describe it, the only one who can change things is the Attorney General himself?

“In practice, the Attorney General occupies a very significant spot, because he controls the mechanism that would allow changes. Therefore I think special attention needs to be paid for the appointment of the next Attorney General—a willingness to conduct reforms should be the key consideration. When I say reforms, I mean simply bringing the institution in line with the rest of the democratic world. I’m the conservative here, not the revolutionary—we need to turn the clock back.”

“In the end, I believe the responsibility must rest on the elected representatives, just as is the case in the rest of the democratic world. I’m not willing to accept a situation where an Attorney General is not willing to let go of his power—it’s human nature not to do so—and the elected representatives therefore divest themselves of responsibility. On this issue, I even have a specific amendment to the Government Law, which will clearly define the authority of the Attorney General and establish that his advice and opinion is not binding. That we need to do.”

Until that happens, we keep running into situations like the discussion of the Infiltrators Law, where the Attorney General refuses to represent the government in court. How do you think an MK should respond to the Attorney General in such a case?

“I would give a simple answer: ‘It’s OK, no need. There’s no lack of lawyers in Israel and we’ll defend ourselves.’ In our study, you can see that in Britain, on all administrative matters, the government is represented by private attorneys. There’s a bank of lawyers who have the right to represent the state, and a professional committee headed by an elected official decides which attorney would best represent them. This idea that I as an elected representative can’t promote my position because there’s a clerk who’s threatening me is very problematic. A minister is supposed to determine what position he takes in court, and if needed who represents him.”

English translation by Avi Woolf.

To receive updates on new articles in English, join Mida on Facebook or Twitter or join our mailing list.