Akiva Bigman takes a look at Religious Zionism’s conservative credentials and finds it sorely wanting.

The American conservative movement is commonly said to rest on three pillars: individual liberty and economic freedom; respect for religion and preservation of tradition; and proud patriotism and a realistic approach to defense. This description, by National Review editor William F. Buckley Jr., one of the founders of American conservatism, hit the nail on the head and served the movement until its great political victory during Ronald Reagan’s presidency in the 1980s.

The connection between these three foundations is not accidental and does not stem only from the fact that they have common enemies. Belief in the conservative Trinity rests on a basic common starting assumption about human nature and the way in which progress works. Conservatives have a pessimistic attitude regarding the nature of humanity. In their view, man is not a perfect, rational creature; he is driven by earthly impulses, desires, and emotions and has a strong self-interested side that responds to incentives and changing circumstances. Friedrich Hayek summarized the roots of thus: “It would be nearer the truth to say that in their view, man was by nature lazy and indolent, improvident and wasteful, and that it was only by the force of circumstances that he could be made to behave economically or carefully to adjust his means to his ends.”

It is thus no wonder that conservatives are deeply suspicious of utopian visions, preferring to rely on social and political systems that have evolved over many years on the basis of trial and error by many generations. From this perspective, the union between support for economic freedom and respect for tradition, on the one hand, and support for hawkishness on defense and patriotic nationalism, on the other, is also understandable: world peace, social justice, and forced equality are examples of the different sides of that same utopian coin that attempts to force a multifaceted and complex reality into a rational, rigid, uniform, procrustean bed that is incredibly naïve and dogmatic ad nauseam.

Conservatives are cautious about attempts to plan the economy, and they therefore support a free market. They fear the consequences of war for the traditional family, so they oppose conflicts that undermine it. They are deeply suspicious of the intentions of foreign countries and peoples, and therefore they prefer to base their national security on independent military capability and not on the good will of other nations.

Above all, a sense of skepticism and uncertainty about man’s ability to understand hovers over conservatism. Like the computer technician in the well-known joke who believes that even if something seems strange, as long as it works, it is better left untouched, conservatives prefer not to presume to engineer things that we do not understand and probably never will. This is also why conservatives generally prefer limited, small governments that work primarily to preserve security and protect property over large governments with a wide span of control over society and a foolish pretension to know how to “improve” it.

Religious Zionism and Conservatism in Israel

There is no real conservative movement in Israel. The various components of what Ronald Reagan called the “three-legged stool” exist in Israel, but no formula has yet been found for uniting a broad enough spectrum of groups into an effective movement.

Many believe that religious Zionists are the key to establishing a conservative movement. The reason is obvious. We can see at first glance that they combine religion and tradition with hawkishness on defense. It looks as if all that remains to be added to their ideology is a free-market agenda—sometimes seen in statements by Education Minister Naftali Bennett—and the religious Zionists, who in any case consider themselves a Jewish elite, could easily become the foundation on which the long-awaited Israeli conservative movement would grow.

Is this really the case, or would a closer look reveal other truths? This may be a propitious time for a careful and meticulous look at the views of the national-religious community to find out, once and for all, whether religious Zionism is conservative, according to our political understanding of the term.

Justice Justice Shall Thou Pursue

Individual liberty and the economic freedom derived from it are among the most important cornerstones of conservatism. The questions of liberty and its limitations surround the citizen in all his endeavors and form the basis of the discussions on various policy questions. Taxation, education, regulation, labor law, media freedom, freedom of expression, and similar questions fill up most of society’s public agenda, and policy formulation in these areas is closely connected to how we perceive individual liberty.

How do religious Zionists regard individual liberty? How do they understand its role in conducting the country’s affairs, the way in which consideration for individual liberty restricts the government, and its importance in the democratic system?

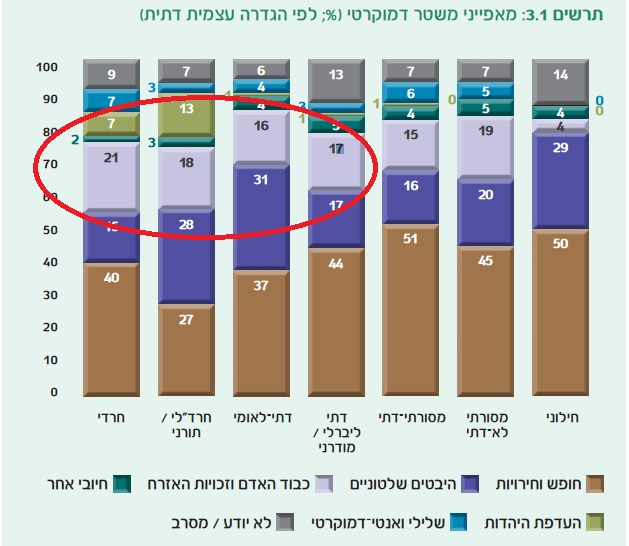

A comprehensive Israel Democracy Institute study on the national-religious community’s views examined how different groups commonly define the essence of democracy. The results are instructive: while half of the wider public perceived preserving freedom and liberty as the essence of democracy, among the three types of national-religious Israelis surveyed, there was a significant relative reduction in recognition of the value of liberty.

Here are the numbers. First, we should emphasize that only an insignificant minority of the national-religious community expresses anti-democratic views. In other words, they accept democracy as a desirable system of government. r in other wordsBut what is democracy to them? It may surprise Israeli civics teachers to discover that despite what they teach their students, the Israeli public, with wonderfully healthy senses, overwhelmingly identifies democracy with liberty. This is true of the secular (50 percent), the traditional but non-religious (45 percent), the traditional-religious (51 percent), and even the haredim, the ultra-Orthodox (40 percent). The national-religious, on the other hand, stand out in their belief that liberty is not the main pillar of democracy: 44 percent of the modern/liberal Orthodox, 37 percent of the national-religious, and 27 percent of the national haredi (the “hardal”) say this. The necessary conclusion is that religious Zionists are less supportive than most other groups of an emphasis on individual liberty as a central part of Israel’s system of government.

Another public opinion poll, conducted by the Beit Hillel rabbinic organization among religious Zionists and using a similar division into sub-groups, demonstrated that the national-religious community supports the social justice agenda quite decisively and sees it as a religious value. On the question whether equal rights is a “Jewish value” there was a difference between the national haredi respondents (36 percent) and other groups (50-59 percent). However, the gaps narrowed on more practical questions. In the national-religious community, an absolute majority sees social justice as “a supreme religious value” (58-72 percent, depending on the sub-group), and an even clearer majority believes that “religious people must take part in the battle over social issues” (69-79 percent). All of these, of course, are opinions that call for large-scale government intervention in the lives of the citizenry, at the expense of liberty.

The unimpressive status of individual liberty among the national-religious is not surprising, given the views of rabbis and other public leaders on the issue. They, too, lean leftward toward what Americans call “progressivism,” or in other words, a belief in big “expert” government that implements conceptions of “justice.” This is contrary to the Republican’s conservative approach, which emphasizes small government and minimal intervention in the lives of individuals and communities.

In an article published in the Journal of Political Ideologies, Moshe Hellinger and Yossi Londin reviewed rabbis’ positions on economics and social justice and examined sub-groups based on the conventional division. In their study, it is difficult to find views expressing clear support for a free-market economy and non-intervention by the state. According to Londin’s findings, most of the rabbis and public leaders who think and write about economic questions have clearly leftist views on the subject. National haredi publications show indifference to the issue.

Another example can be seen in comments by Rabbi Yuval Cherlow, who is viewed as the leader of the national-religious social agenda:

We must establish a state that brings about the redemption and for this reason … the attribute of justice, fairness, morality, sensitivity to the cries of the poor must enter our language … in our current situation, we cannot build the wall of the Lord’s house in a country in which foreign workers do not receive a fair salary, where there is an enormous public-sector gap, and where tax evasion is not seen as a crime.

(“And Where Is the Justice?” Nekuda 251, May 2002 [Hebrew])

Similar remarks were made by Zevulun Orlev when he served as the National Religious Party’s Minister of Welfare and Social Services and asserted that “the neoconservative economic frenzy negates all the values of Judaism.” Professor Shalom Rosenberg, however, appears to have outdone everyone in claiming, in an article published in De’ot, that the essence of a free-market economy and the flourishing of international corporations is a modern form of idolatry in which man creates an abstract entity and becomes enslaved to it. Addressing himself to religious Zionists, Rosenberg demanded that they continue the Jewish tradition from the time of the Hasmoneans, when the Jews knew how to go against the worldwide trend. Now, too, according to Rosenberg, Judaism must serve as an example to the world, stopping the new materialistic idolatry, ceasing the absolute enslavement to profits, and raising the banner of struggle against the free-market economy.

These ideas have also found a home among leading mainstream Zionist rabbis. For example, Rabbi Yaakov Ariel, president of the Tzohar rabbinical organization and the chief rabbi of Ramat Gan, believes that the national-religious community missed an opportunity during the social protests of 2011: “The religious public did not raise the right banner during the social protests,” Ariel stated at a conference on “Social Justice in a Jewish State.” In his view, the religious community should have led the social protests because the “social flag” is a “religious Jewish flag that should be borne proudly.” Ariel personally took part in the protests, and the Ramat Gan yeshiva he heads even set up a protest tent.

On another occasion, Ariel explained that social justice is a principle that should also guide the national leadership: “The people of Israel want a leader, but the sense is that they want a strong leader who is tough on defense, who will save us from the Kassams … We should aspire to leaders who strive for social justice as a principle.”

The social-leftist yearning in religious Zionism reached full organizational expression with the establishment of Bema’aglei Tzedek, whose goal is to promote the values of social justice among the Israeli public. This movement, founded by religious leftists, surprisingly became part of a very broad consensus. A variety of rabbis, representing more or less the majority of the national-religious community, have participated in the conferences it sponsors, especially on fast days. These include Rabbi Shlomo Aviner, Rabbi Mordechai Alon, Rabbi Cherlow, and Rabbi Ariel. Even settlement figures and halachic conservatives such as Aviner and Ariel are joining hands with the economic left.

In one of the first articles published in its journal, Bema’aglei Tzedek defined its principles:

Where is the moral-social voice of Jewish tradition? Could it really be that the religion of Israel has nothing to say about issues such as pension arrangements, workers’ rights, poverty, the accessibility of public places, or attitudes toward the disabled?

(Bema’agalei Tzedek, Issue 1 [Hebrew])

One of the group’s founders, Chili Tropper, appears to have provided the most colorful description of how national-religious energy is supposed to be translated into a practical economic-social movement:

Mass prayers at the Western Wall against the economic decrees, mass demonstrations in Rabin Square against the municipalities’ withholding of wages, and a human chain from Dimona to the Knesset to demand that an adequate basket of medications be provided for the sick and a dignified existence for the elderly.

(“Red Sebastia,” Eretz Aheret, 24 [Hebrew])

This is not mere contemplation. Religious Zionists have been increasingly engaged in questions of economic policy in recent years, and halachic research institutes and batei midrash [Torah study centers] have begun to examine these issues systematically and intensively. Here, too, the study outcomes are far from being economically conservative.

The Keter Institute of Torah-Based Economics is located in Kedumim, one of the hard-core communities of the right-wing settlement movement. The institute publishes frequently on economic issues, and it is clear from its publications that while its researchers have a basic recognition of the obvious advantages of the free market in terms of efficiency and encouraging growth, they believe in massive government intervention in price control and regulation.

Thus, for example, Keter scholars are of the opinion that “one of the roles of the court is control … over market prices” and that we should not rely on free-market forces “against the swindlers.” In their opinion, “there is no question that competition intended to ‘break’ the market and push out the other sellers is strictly forbidden.”

This is not all. “The sale of [basic goods] should be restricted and prices controlled in order to allow even the weakest elements of society to purchase them,” and when necessary, “basic goods should even be subsidized so they can be sold to the entire population.” This includes “not only goods on which our lives truly depend, but any product that people consume regularly for themselves or their family, such as Sabbath and holiday foods (fish, chicken, and the like) and products needed to perform mitzvot (the four species).”

It is not only prices of food and other consumer products that should be controlled. Keter researchers believe that housing, too, is a “basic commodity,” and therefore, “the state is obligated to ensure that the cost of this housing does not increase unreasonably.” While it is preferable to do this by increasing supply, if this is impossible, we should not hesitate to impose “controls over prices for minimal housing.”

Keter Institute scholars also support giving preference to Israeli-made products, unless their price exceeds that of the foreign-made product by 20 percent or more. They oppose tax reductions, which by their nature benefit mainly middle- and high-income earners; oppose cuts in child allowances; support government assistance to needy parents for payment of school fees; believe there should be discounts for student dormitories without age restrictions; and hold that the state must define a “poverty basket” and make sure to provide it to all its citizens, since “ultimately, every working family must get through the month with the necessary minimum.”

It turns out that when the idea that the principle of a free marketi:00-yes.ch with me. te the doc ther time is fine.f extra for really difficult/bad writing.or example.le income earners must be preserved is qualified with “to the extent possible,” this does not leave many areas where it is possible. To dispel any doubts, we should point out that conservatism encourages helping the weak and assisting those with difficulties. However, it refuses to remove responsibility from the shoulders of flesh-and-blood citizens in order to pass it on to the abstract, bureaucratic state. To the conservative, this is a clear moral failing. Furthermore, anyone with even the most basic understanding of economics immediately knows that government oversight and intervention harm the poor first of all. The rich do well in any case, but for the poor, it is the free market that is indispensable, not a suffocating state system that knows, patronizingly and condescendingly, what is good for them.

It should be noted that given the prevailing socialist rhetoric, it is difficult to find religious Zionist intellectuals and public leaders who clearly support liberty and capitalism. One exception is Naftali Bennett, Minister of Education and chairman of The Jewish Home Party, who often speaks in favor of free-market policies. In practical terms, however, even he has worked on this issue in a rather limited fashion, and he tends primarily to emphasize encouraging competition, a fundamentally practical matter, and not the principles of liberty and property rights on which the functioning of a free society is based. Nevertheless, we can hope that this is refreshing news and will perhaps lead to a change for the better.

We conclude this section by quoting Rabbi Benny Lau, one of the heads of the Beit Midrash for Social Justice at Beit Morasha, who makes a magnificent connection between social justice and Jewish mysticism:

Alienation and social segregation, which create separation between people, act as retaining walls for the ceiling that separates Israel from its Father in Heaven. Anyone wishing to see a stream of holiness descending from the Heavens to the earth must break these separating walls.

One can argue whether this is, in fact, the way of the Torah, but one thing is certain: it is not conservatism.

Radicals for the Land of Israel

It is hard to imagine that the national-religious community’s leftward tilt on socio-economic questions surprised many people. What about diplomatic and defense issues? It is well known that religious Zionists are hawkish and have clearly right-wing views. But is the reason for this tendency the same skeptical, conservative realism? Is this a rational assessment of the threats and a plan of action, or is it something else entirely?

When we examine the rhetoric of religious Zionism, we find a confusing mix of realism on defense and radical messianism. This can be seen, for example, in the campaign conducted against the disengagement from Gaza by the Council of Yesha (Judea, Samaria, and Gaza). Security arguments about the dangers of the rise of Hamas and the missile threat to Israel were intertwined with speeches on “the start of the redemption” and prophetic declarations that the plan “will not come to pass.”

When we examine in depth the world-view of the settlement leaders, the torchbearers on diplomatic and defense issues among religious Zionists, we get the strong impression that the claims of realism on defense were intended only to please their listeners and that the main thing is the messianism.

The most prominent example of this is the testimony of Rabbi Menahem Felix, one of Gush Emunim’s founders, in the Supreme Court case regarding the legality of the settlement of Elon MorehRabbi Felix explained to the Supreme Court justices that “the act of settlement by the people of Israel in the land of Israel is the real act that increases security, the most effective and truest.” He went on to say that “settlement itself, however … is not undertaken for reasons of security and physical needs, but by virtue of destiny and Israel’s return to its land.” According to Felix, “the security argument, with all due respect, though its sincerity cannot be doubted, does not in our view change anything.”

To a large extent, it turns out that the motivation for settlement, and in any case the policy that plans it, is not driven by security needs or strategic thinking, but by a messianic vision:

Whether or not the settlers of Elon Moreh are included in the home guard according to the IDF’s plan, settlement in the land of Israel, which is the mission of the people of Israel and the State of Israel, is in any event for the security, the welfare, and the good of the people and the state.

This candor was crucial. The Supreme Court realized that despite statements by Chief of Staff Rafael Eitan, the attempt to settle in Elon Moreh was not the result of security concerns. In any case, it could not be allowed according to the Geneva Convention’s laws of occupation, which permit the use of occupied territory for security purposes.

“I have come to the opinion that the chief of staff’s professional view, in and of itself, would not have led to a decision to establish the settlement of Elon Moreh,” wrote Justice Landau. In his understanding, the reason for government decisions on the issue was different: “The strong desire of Gush Emunim to settle in the heart of the land of Israel, as close as possible to the city of Shechem.”

Justice Landau was not mistaken. The writings and statements of Gush Emunim leaders are full of mystical pronouncements that categorically reject the discussion of worldly policy considerations. “The Master of the Universe has His own politics, according to which earthly politics is conducted,” wrote Rabbi Zvi Yehuda Hacohen Kook. “Part of this redemption is the conquest of the land and settlement in it. This is determined by divine politics, which no earthly politics can overcome.” (In the Public Campaign, p. 112 [Hebrew])

It is no wonder, then, that we find his disciples claiming that all policy formulation should be examined on the basis of the criterion of religious messianism. Scholar Gideon Aran, who spent significant time with Gush Emunim in its early years, collected a wide range of statements by the group’s leaders, which were finally published in his book Kookism. Some of these quotes were on the record, while others were anonymous. A look at the chapters in the book thoroughly and quite persuasively reveals the mystical sides of the leaders’ world-view. Thus, for example, one of them, who remained anonymous, explained to Aran that “foreign affairs and defense are no different from education and culture, or even from Aggadah and Jewish law. It is all Torah and faith. All of these secular affairs are supremely holy … every government decision is a religious matter with intrinsic meaning.” He added that “politics is the test for implementing religion in its entirety. Politics is the Torah and it is faith. That is the complete Judaism, the Judaism of redemption.”

This perspective also places the well-publicized struggles of the 1970s in the correct light: “In Sebastia we did not fight for political principles or merely for security. The war there was about a commandment from Heaven, about advancing the process of redemption, about inner spirituality, the very revival of the sacred.” Everything is so heavenly and spiritual that it is not surprising to find testimony such as this: “Every foothold of ours, every lifting of the hand, opens and closes electrical circuits that illuminate light bulbs in the supernal worlds.”

Therefore, the Gush Emunim people admit, it is difficult for them to conduct a real dialogue with the rest of Israeli society. Another of the leaders explained to Aran that “dialogue is possible only at the edge of the movement, where there is a level of rationality. But inside the movement, meta-rational logic is king.” And there, within the group, arguments based on logic become meaningless: “Our outlook is fundamentally meta-historical, metanatural, meta-social, meta-every-subject-for-discussion.”

Not only is there no dialogue; there is no need to even consider “the actions of gentiles or shallow Jews,” as Rabbi Zvi Yehuda called those who create politics and policy. These people, who are acting in contravention of “the divine plan,” are not important, since “they are null and void compared to the Torah and the divine leadership.”

The elderly rabbi was not the only one who believed this; even Hanan Porat, one of Gush Emunim’s men of action, a politician and member of the Knesset, thought that self-persuasion was needed to change the political reality: “We must teach ourselves: there is no possibility of withdrawal, just as there are no demons in the world” (meeting of Gush Emunim secretariat, 1976).

In fact, Gush Emunim saw settlement as an action that goes beyond not only the rational world of policy, but even the Israeli national question. “Stopping settlement and withdrawing from the territories would be detrimental to our neighbors,” Rabbi Moshe Levinger explained, adding that without the settlements, the gentiles would suffer “a spiritual deterioration that would prevent them from understanding the superiority of our people and recognizing its sanctity.” Thus, with our own hands, “we would block their redemption.” But if we forced our will on them, “they would express their thanks to Israel, which is fulfilling its entire Torah.” And then, when their eyes were opened, “they would contribute to Israel’s security and even to building its Temple.”

When Operation Peace for Galilee broke out, Gush Emunim, in keeping with this world-view, called for settlement in southern Lebanon, “the territories of the tribes of Asher and Naphtali.” As Rabbi Eliezer Waldman explained, the purpose of the entire war was only “to make order between man and his fellow man, between man and his Maker, order among the peoples, order among the countries, order in the entire world.” This is because “it is our responsibility” to prevent a state of “disorder,” which is an “injustice against Heaven.”

We could provide countless other quotations on this subject, but the point is already sufficiently clear: The political and diplomatic leadership of religious Zionism, which spearheads the issue of Israel’s security agenda, expresses radical, messianic opinions based on faith, is attempting to realize a divine utopian vision on earth, and expects a redemptive revolution that it will bring about through its piety.

Such an approach is far from being conservative. What foreign policy can be conducted on the basis of the assumption that the peoples of the world must recognize the greatness of “the celestial beast that walks the earth in the form of a nation called Israel”? How can a defense doctrine be formulated in view of the thought that “every rifle added to the army of Israel is another real spiritual stage, another step in the redemption”? (Both are quotes from Rabbi Zvi Yehuda Kook.)

The conclusion from all this is that even on the diplomatic-security issue, on which the national-religious community has clearly hawkish views, the seeds of messianic radicalism are being laid. This community’s contribution to strengthening the Israeli right and reinforcing settlement and defense arrangements are many, and they are appreciated. But as an ideological movement, as a system of values and political thought, religious Zionism does not have a great deal to offer other than a “meta-every-subject-for-discussion” that is radical and out of touch.

Respect for Tradition and Religious Piety

Thus, we are left with a one-legged stool: the leg of religion and tradition. One leg is still something, but as will become clear from the following, politically, even the religious leg of religious Zionism is not an especially successful ally of conservatism.

Professor James W. Ceaser of the University of Virginia has shown that the religious camp of American conservatism in fact comprises two different groups: those whose political philosophy emphasizes tradition, and those who constitute a religious interest group. According to Ceaser, the traditionalists are secular intellectuals. Their conservative philosophy, whose oldest and most famous expositor is Edmund Burke, leads them to adopt a cautious social policy full of admiration for the cultural enterprise of the generations and its institutions. This includes an emphasis on the supreme importance of family and religion. They translate their ideas into a clear political policy, whose principles include support for small government and a free market.

The religious are different. Their alliance with the conservative movement is primarily a result of a combination of interests, not ideological identification. The United States is based on an ethos of liberty and freedom of religion intended to enable various religious groups to practice their rituals without impediment. This is the institutional basis for American liberty, and the various religious groups have evolved in light of it. The religious join the conservative camp, which is committed to individual liberty and separation of church and state, to ensure that they can conduct their lives as they see fit.

Church leaders do not necessarily identify with the philosophical ideas of Adam Smith and Edmund Burke, but they recognize their political benefit and have made an alliance with them. This is not an obvious connection: religious groups were the last to join the conservative movement that developed in the 1950s and 1960s in the United States, and for good reason. But today, when we add to the equation the New Left’s attempts to use the power of the state to eradicate religion from the public square and promote secular ideas of progress by force, it is almost self-evident that American religious leaders will join the conservatives.

And what about the situation in Israel? Here, things are reversed. Israel is by definition a Jewish state, and its fundamentally socialist government is all-embracing and supplies generous funding for religious services and education. Thus, Israel’s political dynamic pushes the religious away from the camp of liberty and straight into the arms of the left. This was the political genius of David Ben Gurion, who created a complete symbiosis between religion and the state bureaucracy, which is exacerbated by the addition of a messianic ideology that sees state institutions as a metaphysical expression.

The symbiosis between religion and state is so strong in Israel that whenever there is a proposal for budget cuts for religious services or a reform to introduce a bit of competition and consumer fairness to the system, the national-religious (like the haredim) rail against it, claiming that such measures would cause “harm to religion” and that they are nothing less than “anti-Jewish decrees.”

Thus, for example, it was recently claimed that an initiative to establish a conversion system parallel to the rabbinate system “is destroying the Jewish people and the Torah” and that “anyone who raises a hand against the Chief Rabbinate of Israel raises a hand against the Rock and Redeemer of Israel,” no less. In the previous government, when there was talk of cuts to hesder yeshiva budgets (ultimately canceled), religious Zionist leaders declared that “strong action” was needed “to eliminate the deep and disproportionate cuts to yeshivas in general, both Zionist and haredi.” This was because “the world of Torah is the foundation of the people of Israel’s existence”—as if there has never been a Torah world that has not been a beneficiary of government funding.

In the United States, the “camp of faith” is the demographic and financial foundation of the conservative movement. In Israel, however, it is hostile to conservative ideas and is one of the strongest forces connecting Israel’s political right to the economic left and statism. This is because of the different political dynamic and the role of religion in Israel’s national experience.

Three left-wing pillars

Historically, religious Zionism has also been a three-legged stool, but these legs are far from being conservative: religious socialists from Torah ve-Avodah and the religious kibbutz; radical messianists from Gush Emunim and Mercaz Harav; and modern haredim, religious people who are open to Western culture and secular professions, along the lines of the Torah im Derech Eretz movement from nineteenth-century Germany.

The religious Zionist community has many and varied virtues and countless merits. But with all the good will in the world, socialism, radicalism, and dependence on the welfare state are not the ingredients from which a conservative movement is made.

It goes without saying that not all people considered national-religious identify to the same extent with the three ideological pillars described above. The individuals who make up this diverse community display varying combinations of identification with and distance from the legs of the conservative stool. But since politics is a matter of alliances, the fact that advocates for the land of Israel and religion are joining forces with socialist sympathizers in one political movement makes the differences between sub-groups and the opinions of the various individuals much less relevant. Furthermore, this community’s fondness for public opinion leaders who are clearly not conservative also indicates that politically, it does not have a high regard for the foundations of conservatism.

And thus, at the end of the day, for reasons ideological, utilitarian-sectorial, or sociological, the forces that comprise the national-religious community are joining together in a political alliance to create something that is manifestly not conservative.

English translation by Miriam Himelfarb.

To receive updates on new articles in English, join Mida on Facebook or Twitter or join our mailing list.