For fifty years, the anti-war version of the Vietnam War has been the dominant one. It’s past time for a second look.

Introduction

Today marks the fiftieth anniversary of America’s decision to intervene directly in the Vietnam War, when President Lyndon Baynes Johnson authorized the call-up of tens of thousands of American troops to prevent the fall of South Vietnam to its Communist northern neighbor.

The Vietnam War has been the subject of many myths and politically-driven distortions. When I took a course on Vietnam as an undergraduate at Harvard University, both the class and faculty seemed to exclusively echo the position of those who opposed the war, and I was particularly struck by their close-mindedness and contempt toward American soldiers who’d served there.

Having already done a study of the CIA’s infamous Phoenix counterinsurgency program and having received much positive feedback from veterans, I decided to delve deeper into the issue. The more I examined the source material and the more documents I discovered—including a treasure trove of Vietnamese documents and sources for the other side—the more I realized I would have to start from scratch.

Below I will lay out the primary myths peddled by those who opposed America’s initial decision to directly intervene in strength in 1965. [Those interested in learning more are invited to read my book on the subject, as well as the chapter on Vietnam in my book on counterinsurgency].

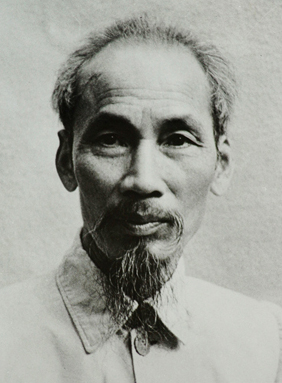

Myth #1: The benevolent Ho Chi Minh

Per conventional descriptions, Ho Chi Minh, Communist leader of North Vietnam, was a largely benevolent nationalist, beloved by the Vietnamese and making only instrumental use of communism for his limited, nationalist goal of reuniting both halves of Vietnam. Historians often make use in this context of the “historic unity” of Vietnam and the ostensibly traditional enmity between Vietnam and China.

But very little of this turns out to be accurate. Far from being a gentle George Washington figure, Ho was a dedicated communist—he praised Lenin’s view of an international revolution, denounced Tito’s separation from the USSR, and personally established and supported communist groups in neighboring Asian states, whose goal was to spread the revolution elsewhere. Furthermore, Ho murdered far more Vietnamese—North and South—through Soviet-style “land reform” and political terror than the US or its South Vietnamese ally ever came close to doing, both before the war and afterward.

His approach to his soldiers’ lives was equally profligate: North Vietnamese and Vietcong casualties were often far greater than US ones. Over half a million communist forces were killed in the war—ten times the American body count. Compassionate, he was not.

Furthermore, the concept of the “historic unity” of Vietnam and its “historic enmity” towards China is also largely false. Far from being eternally united, Vietnam was historically the subject of repeated civil wars between parts of the country—especially between north and south. Moreover, Vietnam was traditionally China’s vassal, only breaking ranks a few times during a thousand years. When the French approached Vietnam, the latter even appealed to China for help. This bond of mutual assistance would continue in the Vietnam War, when China flooded North Vietnam with money, equipment and skilled manpower.

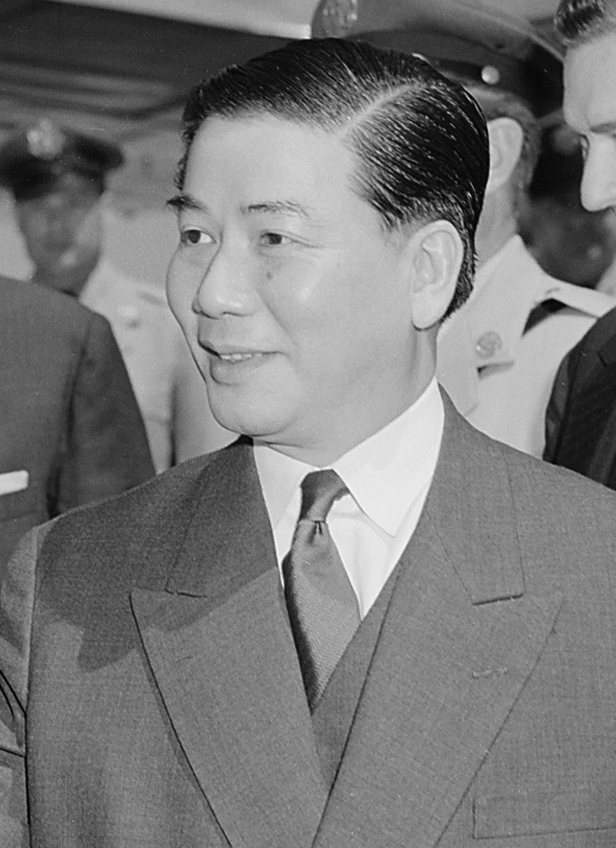

Myth #2: Diem was a Paper Tiger

If Ho Chi Minh is the benevolent national leader of the standard narrative, then its villain is unquestionably South Vietnamese leader Ngo Dinh Diem. Per the standard narrative, Diem was a corrupt, unpopular dictator, who oppressed religious groups and allowed his ineffective armed forces to be led by personal loyalty rather than military effectiveness. The result is that Vietnam was on the brink of collapse by the time South Vietnamese generals launched a coup against him, backed by powerful figures in the US government.

Diem actually commanded much respect among the people of South Vietnam, especially among the peasantry who made up the overwhelming majority of the county. These last saw him as a “good mandarin”—a benevolent authoritarian along the model of a Chinese Mandarin. Although he did suppress political opposition, especially communist sympathizers, he was nowhere near as ruthless as his northern counterpart.

US officials and diplomats greatly erred in trying to force Diem to quickly enact liberal Western style reforms, while not considering the traditional nature of authority in Vietnamese society, which meant that an expedited move to democracy would undermine authority and order rather than lead to a robust democracy. Their mistaken recommendations for deploying forces and the often inadequate monetary support for reforms didn’t help, either. The hostile reporters and diplomats conspired to engineer a coup to topple Diem and replace his government with what they thought would be a more effective regime.

The decision to support the coup was a disastrous one. Not only were Diem and his brother removed, but also the entire cadre of leaders he had cultivated, who were effectively replacing colonial holdovers and keeping the communist forces and agitators at bay. This left a massive vacuum throughout the country, and the North was quick to move in, with the aim of knocking down the now-teetering edifice.

South Vietnam was in danger of falling to communist forces.

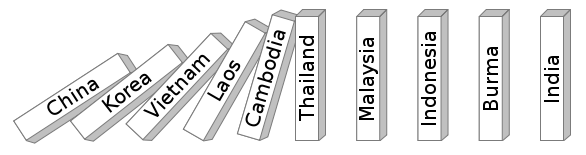

Myth #3: Domino Theory was False

Another myth pushed by those who opposed the war is that there was no truth to the “Domino Theory”—the idea that if one Asian country fell to communism, the others, especially strategically important ones like Indonesia would fall to it like “dominoes.” They point in this context to the actual events of 1975—Vietnam fell to the communists, Laos went red and Cambodia, but no others. There was no compelling reason, therefore, for the US to get involved in 1965.

But this argument ignores significant differences between the political arena in 1965 and 1975. In 1965, many other southeast Asian countries believed very much in the idea of a communist wave sweeping over the region, much like Eisenhower’s Domino Theory. Strategically critical countries such as Indonesia were directly asking America to get involved in Vietnam to halt communist expansion in the region.

There were real and documented fears of senior US and SE Asian officials at the time that the fall of Vietnam would mean not just the direct conquest of other countries, but also of other countries—even Japan—moving left and either tilting pro-Communist or becoming “neutral” and effectively within the communist sphere. As already mentioned, Vietnam and China were working closely together to do just that, cultivating communist movements and preparing expansion.

1975 was an entirely different story. China and Vietnam had fallen out with one another, and Cambodia was undergoing a revolution. The Sino-Soviet split was widening, at least in part thanks to American activity. China, as a result of the Cultural Revolution, was not in the mood to sweep forward as it had wished in 1965. Furthermore, southeast Asian countries, wobbly in 1965, were now secure; Indonesia had long since effected an anti-communist coup and wiped out the communist movement there (largest outside the red bloc)—something which may not have happened if America had not become involved.

Myth #4: A guerilla war

Which leads us to one of the greatest popular misconceptions of all: that the war in Vietnam was primarily a war against guerilla units, a task for which South Vietnam’s forces and especially the large, cumbersome conventional US Army was ill prepared. But this, too, is false.

Anyone who follows the documentary Battlefield, a military reconstruction of Vietnam War Battles, can see that the Vietnam War involved large and powerful conventional forces right from the start. Every major offensive—from the 1965 onslaught to the famous 1968 Tet offensive to the 1975 one which broke South Vietnam—involved large scale conventional battles, featuring artillery, mass infantry and often tanks. As Diem himself once pointed out, the guerillas could be handled, the real threat remained massive conventional invasion, as eventually happened in 1975.

Although both the South Vietnamese and the US made missteps in defeating the guerilla units and destroying their supply lines and base areas in “neutral” countries of Laos and Cambodia, they slowly learned how to defeat the Vietcong. Most importantly, they succeeded in their primary task of blocking a conventional invasion—every single conventional offensive conducted by the Vietnamese failed miserably when the US was in the country.

To sum up, like many chapters in the Cold War, the Vietnam War was a complex story, but not one of which America or its veterans need feel ashamed. They were right to intervene in 1965 and help stop the spread of a destructive and murderous ideology whose true dimensions are still being uncovered in Eastern Europe and throughout Asia. It is time to put the ghosts of Vietnam to rest.

Dr. Mark Moyar is the author of numerous books and articles, including “Triumph Forsaken: The Vietnam War, 1954-1965,” and “Strategic Failure: How President Obama’s Drone Warfare, Defense Cuts, and Military Amateurism Have Imperiled America.

To receive updates on new articles in English, join Mida on Facebook or Twitter or join our mailing list.

When I chose John Foster Dulles as my hero in history I sited the “domino theory” as my reason. NYU’s professor Sidney Hook, a repentant communist, did not appreciate that vulgar notion and awarded me a grade of D in his course The Hero In History. Never really felt bad about that grade since since by then, 1963, I already knew better than to hang out with lefties of any type.