The recent success of BDS have forced a thorough response by liberal Jewish academics. The book tells us as much about them as it does about BDS.

The recent successes and near-successes of the BDS campaign have forced liberal Jews to counterattack • The result: A book which is both a useful anti-boycott resource and a fascinating psychological portrait of an elite • A look into the dilemmas and biases of American Jewish liberal academia

Review of: Cary Nelson and Gabriel Noah Brahm, The Case Against Academic Boycotts of Israel, Wayne State University Press 2015

Gabriel Brahm is the very opposite of the stereotypical academic—unassuming, open-minded, and erudite—and a great drinking partner, besides. He’s the kind of person who would happily spend his days involved in arcane research and teaching forgotten authors, ignoring the “real world” going by. Brahm is the last person whom you would expect to spearhead an effort to edit and publish a hefty book against the BDS campaign.

Indeed, when we met in Tel Aviv to discuss the book, my first question to him addressed this point: Why you, and why now? The boycott campaigns have been going on in some form since at least 2001, if not before. Why the sudden interest? Judging by the articles, many of the book’s contributors sounded like they only recently heard of BDS or anti-Zionist arguments in general.

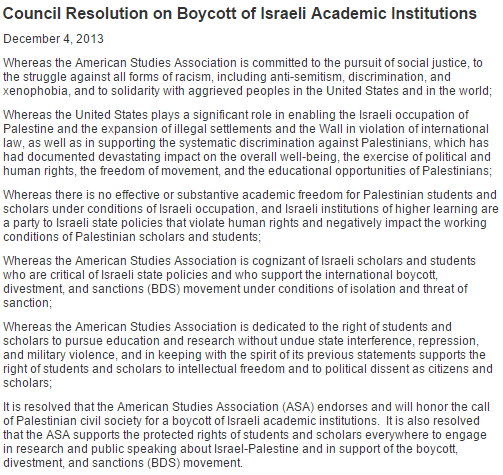

His response was simple: BDS only recently hit the big time, with the recent successful boycott resolution passed by the American Studies Association and a similar but failed initiative at the larger Modern Language Association. That explanation rang true, and it would explain why people like Gabriel would find themselves fighting a campaign which until then didn’t really involve them. As Adam Kirsch pointed out in his review in Tablet, this book is as much the defense of Jewish left-wing academics against what feels like a war directed against them as it is a defense of Israel.

Whom is this book for?

Which brings us to the second problem—whom is this book for? After all, most of the arguments against BDS in the book can be found in blog posts or online articles, in much briefer and less academic form than here.

Gabriel’s response was that, first, this is “what academics do.” They respond to a challenge with a book or a conference. More to the point, this is very much an academic book meant for fellow academics, especially those who are generally uninvolved but might be swayed by BDS arguments in the absence of counterclaims. Given the importance lecturers have in the “fight over Israel” on campus, this makes sense.

More to the point, the book is meant as a printed resource, a reference for anyone in need of information on the history of BDS or arguments against it. Here, the book certainly has something to offer, including a very informative article by Tammi Rossman-Benjamin in which she breaks down BDS supporters by field (English and Literature dominate) and articles by Ilan Troen which dispel the absurd claims of wholesale academic discrimination against Palestinian students in Israel. The book also contains articles and documents which will be of interest to anyone who wants to write a history of BDS from both sides.

Where’s everyone else?

But there’s a very serious lacuna in the book which I immediately noticed and which troubled me more and more as I went further in the book. To put it bluntly: Where are all the right-of-center people? The book’s contributors come almost exclusively from the left and far left, they swear allegiance to liberal and progressive principles, and their points of reference are almost exclusively in that ideological sphere. There is no mention of Jabotinsky, Begin, Burke, or Friedman. Eminent scholar Martha Nussbaum’s conflation of Margaret Thatcher with Nazi sympathizer Martin Heidegger as figures worthy of protest or denial of awards is particularly disturbing and indicative of how many left-wingers see all rightists as nothing but a bunch of Nazis.

This is not just a matter of not getting a “seat at the table” or other forms of sour grapes; the de facto boycott of classical liberal and conservative thought greatly undercuts the message of academic freedom which the book aims to convey. It makes this protest sound less like a fight for a genuine free market of ideas and more of a cry of “shun them, not us – we’re the good guys!”—a protest which rings hollow and has a whiff of hypocrisy. Mutatis mutandis, it reminds me of the communists in the USSR who said nothing (or even approved) when non-communists of all kinds were purged, but were then shocked when their turn came.

This ideological blind spot is even more apparent when it comes to treatment of Israel itself. Author after author insists that, contrary to stereotype, Israelis are not a bunch of right-wing/conservative folk. They harp on the liberal atmosphere on university campuses and even talk of the creation of “transnational” or other forms of identity which aren’t—perish the thought—ethnocentric or nationalistic.

The implicit assumption that being conservative or nationalist is inherently bad is not just deeply insulting but also profoundly counterproductive. A substantial segment—by certain parameters, the majority—of both the Israeli and Palestinian populace is proudly nationalistic and ethnocentric. This segment is filled with people who are no less educated and knowledgeable than their liberal counterparts, and most are not the radical and violent nutcases of common tropes. Maybe if the august contributors bothered to engage their ideas with anything resembling the care they spend countering BDS arguments, they might gain a much better and more sympathetic understanding of both peoples, of the kind no close reading of Judith Butler or Sayid Kashua can replace. It would certainly be more productive for broad based coexistence than tiny and self-selecting “peace programs”.

Beyond protest—what?

This refusal to acknowledge the legitimacy and power of tribal identity beyond asserting the Jewish “right” to it with everyone else results in another blind spot: the presence of tribal identities on the progressive side. This is especially the case with the feminist scholars in the book, who tout the importance of women and the status of women in the Middle East and in the West at every opportunity.

Feminism is very much a tribal identity, complete with mythic pasts, debates on inclusion vs. exclusion into the “group,” and a powerful radical branch which substitutes fighting for equality with virulent hatred of the Other—in this case, heterosexual men. This is pretty much so for all other groups in the PC trinity of “race, class and gender”; every day a new tribe gets added to the LGBT group and there is no end in sight. So it’s not so much tribalism the left-wingers object to as the “wrong tribalism”.

Indeed, there is something a little strange about a group of Jewish academics who are willing to proudly say: “I am a feminist and proud of it!”, “I am a leftist and proud of it!”, “I am for academic freedom and proud of it!”, but as far as I can remember, never “I am Jewish and proud of it!”

Not too long ago, many members of the old Jewish left saw no contradiction between being proudly Jewish and socialist or progressive. Rather than engaging in ingratiating apologetics to “prove” their loyalty to a non-tribal left that doesn’t exist, perhaps some Jewish Pride is in order. But that would require reading the works of the evil right-winger, Vladimir Jabotinsky.

To receive updates on new articles in English, join Mida on Facebook or Twitter or join our mailing list.