The Battle of Galicia is finally given its rightful place as one of the titanic clashes of August 1914 alongside the Marne and Tannenberg.

The greatest proponent of WWI and its ultimate victim, Austria-Hungary’s WWI is a hard story to tell • Dr. John Schindler does so with empathy and great detail • A must-read for any WWI enthusiast

John Schindler, The Fall of the Double Eagle: The Battle for Galicia and the Demise of Austria-Hungary, Summer 1914, Potomac Books 2015.

Telling the story of Austria-Hungary’s First World War is a daunting challenge. It requires knowledge of several languages including German and Slavic dialects. It requires a command of both medieval and modern history and of military affairs. Most of all, it requires an author capable of combining all these into a narrative that is understandable by actual human beings.

Dr. John Schindler, author of the popular intelligence and foreign affairs blog 20committee, is uniquely equipped to do so. A former naval officer and counterintelligence agent in the NSA, Schindler has years of experience analyzing and distilling complicated situations into plain language for various audiences. Although this book formally covers the Battle of Galicia in the beginning of the war, it is in effect a treatise on Austria-Hungary’s war as a whole, and lovers of WWI’s Eastern Front and the old Empire are forever in his debt for his efforts.

A European Anomaly

A common cliché has it that four empires died in the wake of WWI: the Ottoman, the German, the Russian and the Austro-Hungarian. But that’s only half-true. Three of these were reborn: Ottoman Turkey became Republican Turkey, the German Reich became the German Republic and the Russian Empire became the USSR. Only Austria-Hungary died almost without a trace, leaving behind only museums, monuments and a great deal of place names and appropriated institutions.

When it was broken up in the wake of the Great War, nationalists on all sides went out of their way to condemn the Habsburg Empire as an evil tyranny suppressing small nations in the name of the politically dominant Austrians and Hungarians. Even the Hungarians complained that they were too oppressed and restricted by the Austrians. The WWI centennial has seen the opposite: an outpouring of nostalgia for the old empire, with its light touch, its fair administration and its tolerant regime and government. Some even like to compare it to the EU: a multi-national, multi-cultural polity which avoided the evils of nationalism and revolution which bedeviled the twentieth century.

The truth is that it was both, and neither. The multi-national Austro-Hungarian Dual Monarchy was the quintessential showcase of Central European conservatism: the accumulation of thousands of imperfect but workable compromises, which were then followed by thousands more. The monarch was the focus of loyalty, not the state, and both the bureaucracy and army were beholden to him personally. There was no pressure on subjects to assimilate like in the equally medieval Russian Empire: you could be an Orthodox Slav, a Hassidic Jew, a Magyar or a Pole—so long as you faithfully served the monarch, you were just as good as anyone else.

This careful and delicate balancing act was reflected in the Monarchy’s army. Although German was the main language of command, many units spoke their native tongue—be it Italian, Czech, Magyar or otherwise. Indeed, officers were required to be multi-lingual on a scale that would be daunting to your average EU bureaucrat. No other army in Europe or perhaps the world did more to accommodate the varying linguistic and religious needs of their minorities; there were more Field Rabbis in the Austro-Hungarian army than any other army before the establishment of the Israel Defense Forces.

War as an idée fixe

Academics will forever debate whether the Dual Monarchy was truly “doomed” to succumb to the modernizing forces of nationalism and socialism. But as Schindler makes clear, the army’s top brass were convinced this was the case. Schindler paints a detailed and quite damning picture of the General Staff of the Austro-Hungarian Army, especially its head Conrad Von Hötzendorff.

Detached from much of society and seeing both society and war as an abstraction, members of the General Staff constantly fretted over the great dangers which faced the monarchy from irridentist nationalism, socialism and the meddling of foreign powers. While these dangers were real enough, they were greatly exaggerated in the isolated minds of people like von Hötzendorff and his colleague Oskar Potiorek. No doubt the civilian governors, used to the haggling and compromise of the real world, had a different and more sober view. But no-one asked their opinion.

More than any other European power, the Austro-Hungarian military elite saw war as the ultimate panacea. They believed that only with war could the monarchy truly be saved, either through the purifying power of war itself, or by granting the military the power it always craved to clamp down on troublesome minorities and groups.

When Austro-Hungarian heir to the throne Franz Ferdinand was assassinated by a Serbian-backed terrorist group (which Schindler argues was directly supported at least by the local representative of the Russian Empire in Serbia), the Austro-Hungarian military and even civil leadership jumped at the chance to crush Serbia once and for all. There was no possible outcome to the July Crisis save war.

It is therefore ironic that the European power most interested in war in 1914 was also the least prepared. Schindler describes in detail how political haggling, especially on the part of the Hungarians, prevented the Austro-Hungarian Army from being a match for other powers in either manpower or equipment. The Dual Monarchy trained fewer men and retained fewer on active duty than other powers. Its artillery—the most important and lethal arm in the coming conflict—was outdated and outranged by that of the Russian Army, which would always be the Dual Monarchy’s main enemy if it went to war against their Serbian ally.

Even more stunning was the lack of serious, concrete understanding of their enemies. Serbia had just won two major wars in as many years. Even without any serious military intelligence on the Serbs, common sense would dictate that this was a seasoned and experienced enemy to be taken seriously. But command of the offensive against Serbia was given to Potiorek, a man as detached as Hötzendorff who thought that the fight against the Serbs would be a walk in the park. The result was two stinging and humiliating defeats, which Schindler describes in a chapter aptly named “Disaster on the Drina”. But the real catastrophe would come in Galicia against the Russian Army.

The Graveyard of Galicia

Jaroslav Hašek’s unfinished famous satire of Austria-Hungary’s WWI, The Good Soldier Švejk, stopped abruptly with the Austro-Hungarian forces about to meet the Russian Army. This is a shame, because what followed in real life was an event which combined the tragedy and carnage of that war with the kind of incompetent absurdities Hašek so brilliantly pilloried.

If the Austro-Hungarians underestimated the Serbian Army, they were even less prepared to face the Imperial Russian Army. Schindler explains that there were two reasons for this. The first was the betrayal of the Austrian head of counter intelligence, Alfred Redl, who sold out to the Russian Empire and effectively eliminated the Dual Monarchy’s intelligence network in Russia in a story of intrigue and treason worthy of a fictional novel.

The second was what can only be called the strategic incompetence of Conrad von Hötzendorff. Aside from a general idea of attacking, the Chief of Staff had nothing resembling a plan in attacking the Russians: no strategic goals, and no preferred method of attack or serious logistical preparations in case things went wrong. Von Hötzendorff even labored under the delusion that somehow the German Army would come to his rescue when they were busy fighting the French and holding off Russian advances in East Prussia.

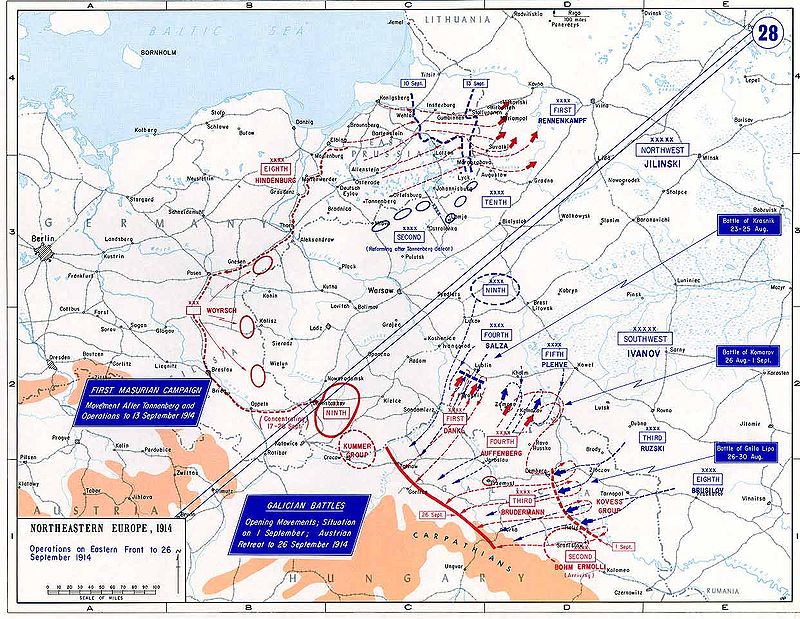

For days, the huge mobilized forces of the Dual Monarchy and Czarist Empire looked for each other across a huge expanse of territory. Aerial and signals intelligence were still in their infancy, so armies still had to rely on 19th century methods like mounted scouts. An alien watching this scene from outer space would have been bemused by the spectacle of hundreds of thousands of soldiers looking around clumsily for the enemy like people groping around a room after the lights are turned off.

Eventually they met in earnest, and the carnage and tragedy that resulted is wonderfully and horrifically described in Schindler’s tome. My heart squeezed up as I read of how unit after unit of the Dual Monarchy’s best trained and most motivated soldiers—Italians, Slavs and others—were sent piecemeal to be destroyed. What the artillery didn’t destroy, the machine guns shot up. What was left of them after that was chewed up by rifle fire and bayonet blades.

With the exception of events at the north end of the battlefront, where Austro-Hungarian forces came close to mauling a Russian Army from both flanks, most of these attacks served no purpose except to add to the casualty lists. To make things even worse, an entire army meant to reinforce the efforts in Galicia had been sent to fight in Serbia, only to be quickly rerouted to Galicia—but at a leisurely, peacetime snail’s pace of the kind that would make any professional commander tear their hair out. Overwhelmed, chewed up and at the end of their logistical tether, Conrad finally saw sense and allowed the army to retreat before being annihilated.

The results of the Battle of Galicia were nothing less than a stunning defeat. The casualty numbers alone—400,000 for the Austro-Hungarians (out of 800,000), about a quarter million for the Russians—give room for pause. Conrad had to give up all of Galicia east of the Carpathian Mountains, including the capital Lemberg. If anyone had any doubt that Galicia belongs alongside the Marne and Tannenberg as one of the titanic clashes of August-September 1914, Schindler corrects this error.

The Other Double Eagle

As one might recognize from this review, Schindler’s book very much tells the story of the Battle of Galicia from the Austro-Hungarian perspective. There are a few voices from the Russian side—first and foremost that of Russian General Brusilov, as well as some Russian prisoners of war—but they are largely a background for the story of the agony of the Dual Monarchy. This is not a criticism of Schindler, who has skillfully combined sources written in several languages to tell this harrowing tale. My point is that this book needs a complementary volume about the Russian side.

I certainly share Schindler’s sympathies with the Dual Monarchy and his condemnation of official Russian persecution of the Galician population. But the Russian Army was not just evil officials and rapacious Cossacks. Most of the army was made up of Russian peasants, many of whom had a weak concept of nationalism and didn’t understand why they were fighting at all. Many of those peasants were Ukrainian. There were Poles and Balts. About half a million Jews served under the Czar, roughly the same as the number of Jews who were expelled as “spies” by the paranoid Russian High Command when the war started to go badly.

What were their feelings in that first horrific month? What did the Ukrainian soldiers feel as they went to “liberate” their brothers? How did the Jews feel, marching under such an openly anti-semitic regime? Their story deserves to be told as well, and I hope Schindler’s work inspires such a parallel effort.

Lost in the First Six Weeks?

Schindler claims in both the summary of the book and in a lecture he gave on the subject that Austria-Hungary effectively lost the war in Galicia that year. The horrendous losses of trained men and officers and the lack of a sizable reserve meant that Austria-Hungary hardly had an army left—more a mass militia. While all sides’ peacetime cadres and forces were effectively gone within the first year of the war, Austria-Hungary’s military machinery was more delicate and not as easily mass-produced as those of the other belligerents.

Nevertheless, in my opinion this is going too far. Indeed, I believe Schindler himself refutes this claim in the final chapter. Austria-Hungary did not lack for capable commanders to reconstitute the army. While the Russian Army had Brusilov, Austria-Hungary had Svetozar Boroevic, who got to work right after Galicia to whip the army back into shape after its dismal performance and would later capably lead the Monarchy’s forces against Italy from 1915 onward. Nor did the Dual Monarchy lack manpower.

No, what really and truly wrecked the army was Conrad. Still obsessed with attacking, Conrad ordered disastrous offensives in the winter of 1914-1915 which cost him hundreds of thousands more casualties he simply could not afford. After Brusilov launched his famous offensive in 1916, the Austro-Hungarian Army was truly finished as an independent fighting force.

None of this was inevitable. If Conrad had been more economical with his men, spending time to build them up and learn lessons from Galicia, the Austro-Hungarian army could have fared much better. Even German help didn’t have to be such a bad thing; Ottoman troops had German officers who helped and gave advice, but the Turkish victories at Gallipolli and Tut were unquestionably their own.

It was not just his conduct of the war but his very insistence on war itself that was the most destructive. Far from eliminating social tensions, the war exacerbated them. Schindler describes how the already paranoid military officers falsely blamed “unreliable” ethnic soldiers for treason and poor performance to cover for their own failures. The ethnic groups in turn increasingly resented the army and then the monarchy itself.

Worse, military rule meant gross mistreatment of civilians. The famously tolerant monarchy now found itself involved in the ugly business of often unjustified summary executions and the internment of thousands in concentration camps, especially when it finally conquered Serbia in 1915. Franz Ferdinand had been against any kind of war with Serbia or Russia, and one can just hear his ghost shaking his head at all this and saying “I warned them.”

In the end, Conrad’s panacea turned out to be a chimera, and the war meant to secure the monarchy’s future helped ensure its doom. In a horrific irony, he did more to harm the monarchy he loved than Franz Ferdinand’s murderers could have possibly hoped to do to the empire they hated. It was an absurdity so great, even Hašek could not have dreamed it up.

To receive updates on new articles in English, join Mida on Facebook or Twitter or join our mailing list.

“the European power most interested in war in 1914”

Schindler makes a huge error here, assuming that Avi Woolf correctly represents the book. Germany, the The Second German Reich wanted the war most of all and had well-developed plans for the war, you do recall the Schlieffen Plan?

This is clear from records of the Austrian cabinet and the records of Count Tisza who warned against pushing the Serbs too much and warned of the possibly dire results of the war. Tisza was the PM of the Hungarian kingdom which was part of the A-H Empire.